Updated November 25 2025

In what is a departure from my usual topics of astronomy and space science, I’ve written a series of posts on the transition to electric vehicles. In this post I’ll discuss the issues of the lifetime of EV batteries, their lower energy density compared to traditional hydrocarbon fuels and the secondhand value of EVs.

Issue: Lifetime of batteries

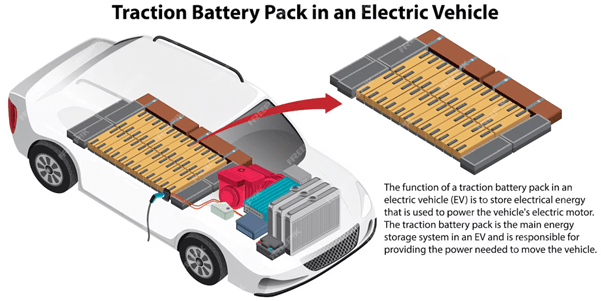

The fuel tank which stores the energy to power an ICE vehicle should last the lifetime of the vehicle. This is not true of its the equivalent energy store in an EV, the battery.

Anyone who’s had an appliance with a rechargeable battery will know the battery has a finite lifetime. Over time the amount of energy it can store gradually falls. After five years of typical use a mobile phone battery often needs to be replaced because it can’t hold enough energy to function correctly.

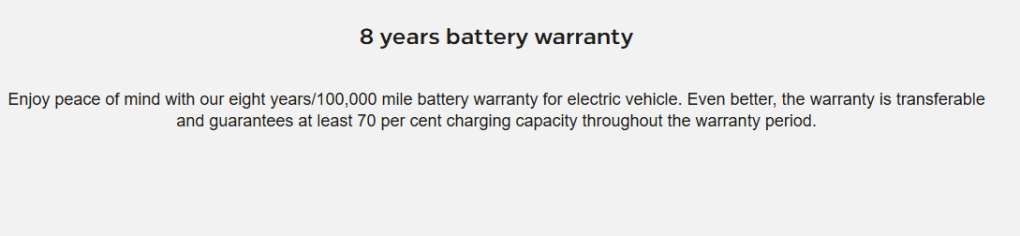

The lifetime of lithium-ion batteries found in EVs have improved over recent years. For example, Vauxhall guarantee that the battery on their Electric Astra will be able to hold at least 70% of its original capacity i.e. 38 kilowatt-hours, for 8 years or 100 000 miles, whichever comes first. This of course does not mean that we would expect the Astra battery to fail after 8 years or 100 000 miles.

(Source https://www.vauxhall.co.uk/owners/insurance-and-warranty/warranty.html)

The battery life can be extended by keeping it between 10% and 80% of its full charge whenever possible and only fully charging when it is essential for longer journeys. Avoiding ultrafast charging will also improve an EV battery’s lifetime. These considerations don’t apply to ICE vehicles. The level to which the fuel tank is filled doesn’t affect its lifetime neither does the speed at which it is filled up at filling stations.

Issue: lower Energy Density

The energy density of a substance or an object is normally expressed as the amount of energy per unit volume, but in this post, I will use an alternative definition of the amount of energy per unit mass. The mass of a 50 kWh lithium-ion battery is about 200 kilograms and so its energy density is 0.25 kWh per kilogram. In all electric vehicles the battery pack takes up a much greater space and weight than the fuel tank in a vehicle powered by an ICE. The large mass of their batteries is the reason why EVs are considerably heavier than their ICE equivalents.

Over the coming decade, improvements in battery technology will undoubtedly lead to higher energy densities. Lithium-ion batteries are a great improvement on the older technology of lead-acid rechargeable batteries. For example, a one kWh lead-acid battery weighs 25 kg, giving an energy density of only 0.04 kWh per kilogram. A bank of lead-acid batteries storing 50 kilowatt-hours of energy would weigh 1.25 tonnes, making its use impractical in a small family car.

By comparison, burning one kilogram of petrol releases 12.5 kWh of energy. The energy density of petrol is fifty times higher than a typical lithium-ion battery in an EV.

As battery technology improves higher energy densities will be achieved. Solid state batteries in which the electrolyte is a solid, rather than than a liquid or a gel, looks a promising new technology which could deliver higher energy densities. Although at the moment it is early days and there are no EVs for sale with solid state batteries. An energy density of 0.5 kWh per kilogram would allow a small family car like the Vauxhall Astra to be fitted with a 100 kWh battery giving it a realistic real world range of at least 300 miles. If at some point in the future an energy density of 1 kWh per kilogram could be achieved it would allow a 200 kWh battery giving a range of 600 miles.

Even so, it will never be possible to make batteries with the same energy density as traditional hydrocarbon fuels such as petrol, diesel and LPG.

Issue: Costs of EV batteries

Even though they have fallen over recent years, the costs of EV batteries still remain considerable. A replacement battery for the electric Vauxhall Astra costs about £ 6000 ($7500). On top of this figure are the costs of the labour for disconnecting the old battery and installing the new one, so the total cost to replace the battery is around £ 6500 ($8125). This could well have a significant effect on used car values.

Effect on used car values.

There is a large market in the UK for used cars which are relatively old and have a significant mileage. Until early 2023 I owned a petrol-engined Ford Focus (shown below). I bought it when it was two years old and during the 11 years I had the car, it needed no major repairs. When I sold it, it had done 160 000 miles, and I suspect I could have kept the car for another 3 years without any major issues. I only changed it because I wanted to have a car with automatic transmission and a built-in reversing camera.

If someone buys a 10 year old EV which still has its original battery, then the new owner might have to pay a large sum of money for a replacement battery during their ownership. This may have a significant effect on the values of used EVs. Currently, a private seller would expect to receive around £5000 for a 10 year old (i.e. 2015 model) petrol-engined Vauxhall Astra with an average mileage.

If we go forward ten years from the present to 2035 a private seller might find that a 10 year old (i.e. 2025 model) electric Vauxhall Astra would be worth very little if it still had its original battery. The potential cost to the new buyer of having to replace the battery during their ownership would make the car effectively worthless.

On the other hand, it is worth making the point that, although EV batteries are typically guaranteed to hold 70% of their capacity for 8 years/100 000 miles, this does not mean of course that a battery will fail when it is ten years old. Its lifetime would depend on how well the battery had been treated (e.g. if it had been frequently charged at a very fast rate). EVs are new and there just isn’t enough data on the lifetime of batteries. If it were to turn out that EV batteries had significant usable capacity when they were fifteen years old, it would be less of an issue.

In summary (over the last four posts)

The move away from ICE powered vehicles to EVs makes sense from an environmental point of view. But there are still significant challenges remaining – none of which are showstoppers. The high costs of public charging is an economic issue which could be overcome. The UK government could make a positive move by reducing the rate of tax paid on electricity consumed at public chargers. Although this would lose billions in tax revenue

Technological issues such as the lower energy density of EV batteries compared to fossil fuels, which means that EVs are inevitably heavier compared to the equivalent ICE vehicles, and the longer refuelling times cannot be completely overcome and will have to be accepted as we make the transition. Howver in the next decade solid state batteies may well deliver big improvements.

In the UK the infrastructure doesn’t yet exist to deliver the amount of electric power needed if we are to have large numbers of faster chargers at public car parks, on street parking and the car parks at shopping centres, entertainment venues, hotels and restaurants. But given time and investment this could be built.

Even though prices will fall, it is likely that the cost of replacing the battery in an EV is always going to be high, and this will be reflected in the second hand value of EVs which still have their original batteries.

It is sometimes stated that hydrogen-powered vehicles, which do not have some of the disadvantages of EVs may become a widely used zero-emission alternative. However, there are many drawbacks of hydrogen-powered vehicles which, at the moment, prevent their widespread adoption and I’ll discuss these in my next post.

Other Related Posts

I hope you have enjoyed this post. It is part of series of five(listed below) about the transition to zero emission vehicles and some of the challenges it poses.

- Understanding why we are shifting away from the internal combustion engine.

- The limited range of electric vehicles and the relatively high cost of public charging.

- Lack of available of public charging and the relatively long time it takes to charge an EV battery.

- Some of the challenges of EV battery technology and their high cost.

- Could hydrogen-powered vehicles be an alternative to electricvehicles?

Also, if you’ve not done so already, please take a look at the Explaining Science YouTube Channel.

The popular astronomy playlist may be of particular interest to those of you without a strong scientific background.

then there’s the environmental and financial cost of dead battery disposal, which is worrying. For me, the immediacy of the need to move from fossil fuel emission weighs heavier, but it’s surely a tough one.

LikeLike

Yes there are msjor issues with the transition ahead, and I didn’t even mention the disposal of dead batteries (!). But I just can’t see anything happening to prevent the phase out of new ICE cars and vans by 2035

LikeLike

A very interesting set of articles. Just one footnote for this one. Although replacing a battery would add a significant cost to ownership, regular maintenance costs of EVs are very low compared to their ICE counterparts, because of the simple fact that they do not have engines! Also, if you are able to charge regularly at home, then driving an EV is cheap too. So it would be wrong to conclude that the cost of ownership of an EV is higher than an ICE car.

It may be in some cases.

On the other hand, my previous BMW needed replacement valves, clutch and fuel injector in the three years I owned it, making it an extremely costly car to keep on the road!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Steve

#You make some interesting points. I should probably research an article on the TCO of an EV versus an ICE vehicle

LikeLiked by 2 people