Geostationary orbits – the basics

A geostationary orbit is a circular orbit where:

- the orbit is in the plane of the Earth’s equator

- the satellite orbits in the same direction as the Earth’s rotation (i.e. looking from the North Pole it is anticlockwise)

- the orbital period is exactly the same as the Earth’s rotation period 23h 56 m 4.1 sec

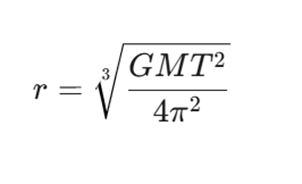

The radius of any circular orbit around a massive body is given by the following equation.

Where

- r is the radius of the circular orbit (i.e. the distance from the centre of the massive body to the satellite) in metres.

- G is Newton’s gravitational constant (6.674×10−11 N⋅m2/kg2).

- M is the mass of the central body in kilograms.

- T is the orbital period in seconds.

For a geostationary orbit around the Earth the radius works out at 42164 km.

Communications satellites are often placed in a geostationary orbit so that Earth-based satellite antennas do not have to move to follow them but can be pointed permanently at the position in the sky where the satellites are located. Weather satellites are often placed in geostationary orbits for real-time monitoring and data collection, as are navigation satellites used to enhance GPS accuracy.

If we calculate the radius of a lunar stationary orbit, because of the Moon’s slow rotation, it comes out at 88453 km.

Such an orbit would be outside the Moon’s sphere of gravitational influence, its Hill sphere, making its existence impossible.

The Hill sphere.

If you consider two bodies in which the lighter one orbits the more massive one, e.g. the Moon orbiting the Earth or the Earth orbiting the Sun or the Sun orbiting the centre of our Milky Way galaxy, then the Hill sphere of the lighter body is the region of space where its gravity is the dominant force and a satellite can have a stable orbit around it. It is named after the American astronomer and mathematician George William Hill (1838 – 1914). Hill was able to quantify the gravitational sphere of influence of an astronomical body in the presence of other heavy bodies. While he didn’t formally name the area around a body where its gravity dominates enabling it to capture satellites “the Hill sphere”, he published the idea in 1878 in an influential paper [1] and it later became known as the Hill sphere as a tribute to his work.

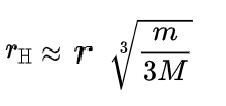

Mathematically, for a near circular orbit, the approximate radius of the Hill sphere is given by the following equation.

Where:

- rH is the radius of the Hill sphere

- r is the distance between the two bodies

- m is the mass of the lighter body

- M is the mass of the more massive body

For the Earth-Sun system, the radius of the Earth’s Hill sphere is approximately 1.5 million km. For the Earth-Moon system, the radius of the Moon’s Hill sphere is approximately 60 000 km. Because the orbit of our hypothetical lunar stationary satellite is well outside the Moon’s Hill sphere it would not be a stable orbit. The satellite would leave the Moon’s gravitational influence and go into orbit around the Earth.

Reference

Hill, George William. “Researches in the Lunar Theory.” American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 1, 1878, pp. 245–260.

Related Posts

Why lunar stationary orbits are imposible due to the relative sizes of the Earth and the Moon’s Hill spheres