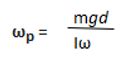

If we look again at the simpler case of the spinning top, discussed in the main article, the torque caused by the force of gravity causes it to precess. The rate of precession about the line OZ is given by the formula:

Where

ωp is the angular velocity of the precession measured in radians per second. To convert from revolutions per second to radians per second multiply by 2π.

- m is the mass of the top

- g is the acceleration due to the Earth’s gravity

- d is the distance between the centre of mass of the top and the origin

- I is a quantity known as the moment of inertia.

- ωp is the angular velocity of the precession measured in radians per second.

The derivation of this formula is normally covered in the first year of an undergraduate physics course and I will not repeat it here. However, for any readers wishing to find out more, the following links are useful.

http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/top.html

There is also an interesting video which describes in simple terms how precession works without using any mathematics.

Example

If we consider a top having: diameter of 5 cm, mass 80g, rotating at a speed of 100 times a second and the distance between the bottom of its spindle and the centre of mass of 15 cm.

So putting these values into the formula above

- m = 0.08 Kg,

- g = 9.8 metres /sec2

- d= 0.15 metres

- ω = 2π x 100 ≈ 628 radians /sec

- I= ½ x 0.08 x 0.0252 = 2.5 x 10 -5 kg metres 2

gives a precessional angular velocity ωp of 7.5 radians /sec or, dividing by 2π, 1.2 revolutions per second.

In the ideal case, if there were zero friction at the bottom of the spindle and zero air resistance, then the top would continue to spin and precess at the same rate indefinitely. In reality, this is not the case, the top will gradually slow down as it loses rotational energy, start to become unstable and then eventually fall over.

Precession of the Earth’s axis.

In the case of the Earth the torque is exerted mainly by the Sun and the Moon and arises because the Earth is not a perfect sphere and is slightly flattened having an equatorial bulge. The diagram shows that the pull of the Sun’s gravity on the bulge tries to change the orientation of the Earth’s spin axis so that it is at a right angle to the plane of its orbit. Because the Earth is spinning this torque will cause its axis to precess for the same reason that the spinning top precesses.

However, unlike the simpler case of the spinning top when the torque due to the Earth’s gravity remains constant, the torque due to the Sun on the Earth varies throughout the year

- It is strong in June (marked A in the diagram) when the North Pole is pointing towards the Sun and the centre of the bulges on either side of the Earth deviate greatest from the line joining the centre of mass of the Earth to the centre of mass of the Sun. This is shown as a dotted line in the diagram.

- It is also strong in December (marked B) when the South Pole is pointing towards the Sun and the centre of the bulges on either side of the Earth deviate greatest from the line joining the centre of mass of the Earth to the centre of mass of the Sun. This is also shown as a dotted line in the diagram.

- At the equinoxes in September and March (marked C and D) the centre of the bulges on either side of the Earth lie on the line joining the centre of mass of the Earth to the centre of mass of the Sun. In this case the net torque is zero.

It can be shown mathematically that the strength of the torque of the Sun on the Earth varies as the inverse cube of the distance between the Earth and the Sun. Because the Earth moves in an elliptical orbit and is closest to the Sun in early January and furthest away in early July, this also causes an additional variation in the torque resulting in the torque at the December solstice being stronger than it is at the June solstice.

The Moon’s orbit around the Earth is inclined at an angle which varies between 18.3 and 28.6 degrees to the Earth’s rotation axis, marked as θ in the diagram below. This means that the Moon also exerts a torque on the Earth. Even though the Moon’s gravitational pull is much weaker than that of the Sun its proximity to the Earth means that the average torque is approximately twice that due to the Sun.

- It is strong when the Earth’s South Pole is pointed towards the Moon (marked A in the diagram) and the centre of the bulges on either side of the Earth deviate greatest from the line joining the centre of mass of the Earth to the centre of mass of the Moon. This is shown as a dotted line in the diagram.

- It is also strong 13.7 days later when North Pole is pointed to towards the Sun and the centre of the bulges on either side of the Earth deviate greatest from the line joining the centre of mass of the Earth to the centre of mass of the Moon. This is also shown as a dotted line in the diagram.

- At the intermediate points (marked C and D) the centre of the bulges on either side of the Earth deviate lie on the line joining the centre of mass of the Earth to the centre of mass of the Moon. In this case the net torque is zero.

Because the Moon moves in an elliptical orbit, this also causes a variation in torque. In fact, as the eccentricity of the Moon’s orbit around the Earth (which averages around 0.052) is greater than that of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun (0.0167), this variation is much greater

(The eccentricity, which is usually given the symbol e is a measure of how elliptical an ellipse is. It is defined as e2 = 1 – (b2/a2) where a is the long axis and b is the short axis of the ellipse).

A further complication is that the eccentricity of the Moon’s orbit isn’t fixed but varies between 0.0255 to 0.0775

Variation of the Moon’s orbital eccentricity – adapted from (Espenak 2012)

Although the torques due to the Sun and the Moon are the main factors in the Earth’s axial precession there are other elements which need to be taken into account. In particular, the torques from the planets, especially Venus which can approach as close as 38 million km to Earth. Because of the complexity and number of other factors contributing to the total torque on Earth it is not possible to calculate the rate of precession exactly and, in any case, it fluctuates over time. The current value from astronomical observations is that the Earth’s axis completes a full circle every 25 771 years.

References

Espenak, F (2012) Eclipses and the Moon’s orbit, Available at: https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEhelp/moonorbit.html (Accessed: 20 September 2020).

Wielen B, Jareiss H, Dettbarn C, Lenhart H, Schwan H (2000) Polaris: astrometric orbit, position, and proper motion, Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0002406 (Accessed: 8 September 2020).