After the Soyuz spacecraft failed to get into orbit on 11 October 2018, it looked like Soyuz flights to the ISS might be on hold for a period of time and that the ISS would even need to be temporarily abandoned. Luckily this hasn’t happened. The next Soyuz will fly to the ISS on 3 December 2018.

Soyuz MS spacecraft docked to the ISS – image from NASA

Although this is good news for now, the future of the ISS is uncertain beyond 2024. In February 2018, the White House indicated that NASA would cease to receive government funding for the ISS by 2025. If this is enforced, billions of dollars will need to come from private companies, and other countries benefiting from the ISS will need to make a much greater contribution to the costs.

Although the ISS is labelled as an international project, in reality most of the costs of building and operating it have been born by the American taxpayer. Each year it remains in orbit, NASA allocates roughly half of its total human space flight budget to ISS operations – an expenditure that limits its ability to fully fund development of manned spacecraft to visit the Moon and other destinations beyond low Earth orbit.

Is privatising the ISS realistic?

In reality it is difficult to see how private companies would pick up America’s contribution towards running the space station, which is currently running at about $4 billion per annum.

Although in recent years NASA has taken steps to commercialise the ISS, a recent NASA audit report was highly sceptical about NASA being able to run the ISS without government support

‘NASA’s current plan to privatize the ISS remains a controversial and highly debatable proposition, …. it is questionable whether a sufficient business case exists under which private companies can create a self-sustaining and profit-making business independent of significant Government funding.

In particular, it is unlikely that a private entity or entities would assume the Station’s annual operating costs, …. Such a business case requires robust demand for commercial market activities such as space tourism, satellite servicing, manufacturing of goods, and research and development, all of which have yet to materialize. Candidly, the scant commercial interest shown in the Station over its nearly 20 years of operation gives us pause for thought about the Agency’s current plan.’

According to this report America pays 77% of the ISS operating costs. It is unlikely that other nations would want to significantly increase their contribution if the US Pulled out. The European Space Agency (ESA) is working with the Chinese Space Agency to fly European astronauts on the new Chinese Space Station, which is planned for operation in 2023, so is unlikely to want to pay more towards the ISS.

What happens next to the ISS?

Assuming that private companies do not take over the running of the ISS over the next 5-10 years I can see four options.

Option 1: Continue with US government funding beyond 2024.

One thing to bear in mind with this option is that the ISS has already exceeded its original lifetime. At the start of the ISS programme in 1998, it was expected to be decommissioned in 2015. In 2011, as construction was nearly complete, this was extended to 2020. In 2014, it was further extended to 2024.

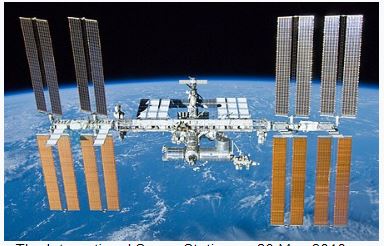

The ISS – Image from NASA

By 2024 some of the components in the ISS will be almost 30 years old and nearing the end of their operational lifetimes. Although this does not mean that there will be a major failure in the ISS, it is inevitable that as the ISS gets older there will be increased risks to the crew due to ageing hardware and equipment.

If this option were chosen, as discussed previously, it would mean that NASA would have less money to develop spacecraft to go beyond low Earth Orbit.

Option 2 Perform a controlled re-entry.

When the decision is taken that the ISS has reached the end of its lifetime, a rocket would dock with it. The rocket’s thrusters would fire to lower the ISS’s orbit, from its current altitude of 400 km to around 100 km. At this altitude there is sufficient atmosphere for air resistance to rapidly slow it down. The ISS would break up into many pieces each moving so fast that friction would generate enough heat for most of them to burn up in the atmosphere. However, a few larger parts might survive to hit the Earth’s surface.

A controlled re-entry would ensure that the ISS’s final disintegration would take place over an unpopulated area. The Russian space station MIR, which had a mass of 132 tonnes, was destroyed in a controlled re-entry over the South Pacific in 2001.

Path following by MIR during its re-entry – image from Wikimedia commons

The cost of this option would be hundreds of millions of dollars. It could not be done by America alone, it would also need agreement from Russia, the European nations and Japan who legally own some of the ISS modules.

Option 3 When the ISS reaches the end of its lifetime it is abandoned and left to its fate.

At the ISS’s altitude (400 km), there are sufficient traces of the Earth’s atmosphere to cause it to lose energy as it moves against air resistance. This causes the ISS to very gradually spiral down to Earth. The distance a satellite drops in altitude is known as its orbital decay and for the ISS is 2 km per month. This is the reason why the ISS needs to be periodically pushed upwards by firing its boosters or those from attached spacecraft.

If the decision were taken to abandon the ISS and stop boosting it upwards, it would return to Earth within a few years and as it hit the thicker atmosphere it would disintegrate. However, there would be little or no control over where the disintegration happened. There would a small risk that debris could land over a populated area and cause damage to people or property. This is what happened to the American space station Skylab which was abandoned in 1974 and re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere in July 1979.

Skylab weighed 77 tonnes (compared to the 420 tonnes for the ISS) and is to date the largest ever satellite to return to Earth in an uncontrolled re-entry. The inclination of Skylab’s orbit was 50 degrees to the Earth’s equator, which meant that anyone between latitudes 50 degrees North and 50 degrees South was in danger from being hit by debris, although the actual risk of anyone coming to harm was exceedingly low. On July 11 1979 it re-entered and disintegrated over a sparely populated region of Australia.

No one was hit by debris, but some large pieces of Skylab hit the Earth’s surface including part of an oxygen tank (shown below) which was found 15 miles southwest of the town of Rawlina, Western Australia.

President Jimmy Carter issued the following message of apology, when it was clear that Skylab hadn’t fully broken up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

‘ I was concerned to learn that fragments of Skylab may have landed in Australia. I am relieved to hear your Government’s preliminary assessment that no injuries have resulted. Nevertheless, I have instructed the Department of State to be in touch with your Government immediately and to offer any assistance that you may need.’

From the New York Times

Although this option is the cheapest, given the size of the ISS and risk of large pieces hitting a populated area, it is unlikely to be chosen.

Option 4 boost the ISS into a higher orbit.

At the end of its lifetime, a booster is attached to the ISS to place it into a higher orbit where the atmospheric drag is very low. If the ISS could be boosted to an altitude of 900 km if would remain in space for about 1000 years This option is likely to have similar cost to option 2 but gives the interesting possibility that future generations would be able to visit the ISS. Eventually, it might become an historical site where extremely wealthy space tourists would travel to.

An opportunity for international cooperation?

The ISS provides a platform in which humans can spend a long period of time in near zero gravity. This research is important because, in the next few decades, when astronauts travel to Mars they will have to spend at least six months in zero gravity when travelling to the red planet and a further six months on the return journey. An extension of the ISS’s lifetime to 2028 or beyond would enable NASA to continue in-orbit research to prepare for future long duration space missions.

As mentioned in a previous post, China has already successfully launched two small space stations, Tiangong 1 and 2, which have been visited by Chinese astronauts. It is planning to launch a much larger space station in 2022 and the facility will be open to foreign astronauts. ESA already has an agreement with China to send astronauts to the new Chinese Space Station once it is operational. However, there is no cooperation between America and China in manned spaceflight. In 2011 Congress passed a law prohibiting any official American contact with the Chinese space program, citing national security concerns. This policy has hardened over recent years and NASA currently prohibits any of its engineers or scientists from working with China.

To me what should happen, although it might be politically very difficult, is for America and China to sit down together and to come to an agreement making America a big partner in the new Chinese Space Station. Perhaps there should be an International Space Station Mark Two?

This space station would be truly international with all the major nations of the world contributing, rather than being America-led and [largely] American taxpayer funded.

2024 huh? $4 billion a year is roughly $ 30 a year per tax payer. Is the US govt so cheap that they cant keep that going for the benefit of humanity? Not to mention just plain bragging rights that the ISS is basically ours? I think they should keep it running with no plans to stop it running. We need more space science. How are we going to test new space techs that will take us off this planet if we dont have a place to do it it. So lame.

LikeLike

You make a very interesting point, I am not sure that everyone in the current US government would agree ! 😉

I am also aware that since I wrote this post back in November 2018, I probably need to write a revised version in the next year or as things develop

LikeLike

[…] space post-2024. Articles like The Options for the Future of the International Space Station and The future of Internation Space Station pointed out towards decommissioning the station as the best alternative. They discuss how private […]

LikeLike

I would think the only two options would be to control the re-entry or push it out further to save for posterity. I prefer the latter for sure. At least then it would release more funding for NASA to use elsewhere. As for US and China getting together peacefully I am highly doubtful that will happen but will continue to hope that one day we might be able to get along at least in that one endeavor.

LikeLike

I agree with you cooperation between US and China in manned space exploration would be the logical thing to happen. However, in the current political climate it is highly unlikely in the near future.

It will be interesting to see what NASA does (and the the US government stance is) in 4-5 years time when the Chinese Space Station is launched (with the European nations as partners)

,

The Science Geek

LikeLike

Great article! I wonder if they’d use existing hardware like the European ATV to deorbit the ISS, or if they’d design a custom stage to do so.

LikeLike

Thank you, interesting question. I suspect, that because of the ISS’s large mass, NASA/ESA/JAXA/the Russians would need to build a custom stage

LikeLike

Personally, I would prefer that it was NOT de-orbited and destroyed by burning up in the Earth’s atmosphere. I would much rather that it was shifted to a higher orbit where it could remain as monument

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Let's Get Off This Rock Already! and commented:

Very interesting article from the Science Geek, about what exactly we’re going to do about that vast, aging, and expensive piece of hardware we’ve got sitting in LEO. My personal hope is that we can boost the ISS into a high orbit and use it as a museum; failing that, a controlled reentry would make for some interesting fireworks.

LikeLike

[…] Source link […]

LikeLike

Door number four for me too. 🙂 … I do wonder what unofficial communication is going on though.

LikeLike

I like that fourth option best. The I.S.S. is almost like the eighth wonder of the world, at least in my mind. It would be nice to preserve it for future generations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too!

It is the most expensive structure every built and it would wonderful if it were kept for posterity

LikeLiked by 2 people

Meanwhile it is 1984 in China. It has it’s own plans, but America is competitive. That is not bad anyhow. Competition means progrwss. How about the European Union, the biggest economy of the world? Space-exit I’m afraid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An interesting point

LikeLike

Interesting. Thanks for sharing this.

LikeLike

Thank you

LikeLike