Updated November 25 2025

In what is a departure from my usual topics of astronomy and space science, I‘ve written a series of posts on the transition to electric vehicles. This is second in this series. In this post I will discuss the issues of the limited range of EVs and the high costs of public charging.

Issue: the limited range of EVs.

One of the key issues with electric vehicles is that despite, recent improvements in battery technology, their range is shorter than the range of an equivalent ICE vehicle.

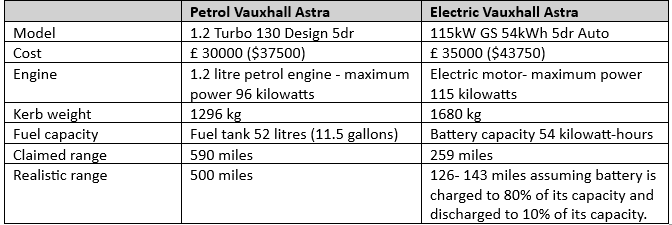

To give a comparison between electric and internal combustion engine vehicles, I have used the example of the Vauxhall Astra. A small family car which is very popular in the UK. This is made by Stellantis and is available in electric and petrol-engined versions.

Despite this being a scientific blog, in this table and throughout these posts, I have used imperial units. These are still widely used within the UK, where people measure distances in miles and fuel economy in miles per gallon (or in the case of EVs miles per kWh). Gallon means a British gallon which is 4.54 litres.

As well as its shorter range the table illustrates that the electric Astra is more expensive and considerably heavier than the petrol model

Petrol model range

Under test conditions, the manufacturers claim an average fuel consumption of 51.4 miles per gallon. In reality, most drivers will achieve less than this. 46 miles per gallon is a reasonable estimate. Although the fuel tank has a capacity of 11.5 gallons, a driver would expect to fill up before the tank had less than half a gallon left. This gives a realistic range of about 500 miles.

Electric model range

The manufacturers claim a range of 259 miles. However, this was achieved under ideal test conditions and does not reflect real world driving. Drivers of electric vehicles typically get ranges which are far less than those claimed by the manufacturers. To get a more realistic range I went to the website of Motability (https://www.motability.co.uk/). This is a UK charity which leases cars and other vehicles to people with a disability. They own a fleet of 700000 cars – by far the largest fleet in the UK and one of the largest in the world.

Motability state

- Different things affect range, like weight, where you’re driving, how you drive, and even the weather.

- Cold weather can lower range by 5 to 20% for electric cars.

- When you add things to your car like luggage or roof boxes, or even just more passengers, this makes your car heavier. The heavier your car, the more energy it needs to get from A to B

- If you’re using features in your car, like playing the radio, this will have a slight impact on your range.

- A good rule of thumb is to knock about 20% off the ‘stated’ range of an EV. This will give you an idea of how many miles you can comfortably cover on a single charge.

Motability give a realistic real-world range for the electric Astra of between 180 and 204 miles. However, to optimise battery life, an EV battery should not be allowed to fall to less than 10% of its capacity and it should not be frequently charged to more than 80%. This gives a day to day range of between 126 and 143 miles.

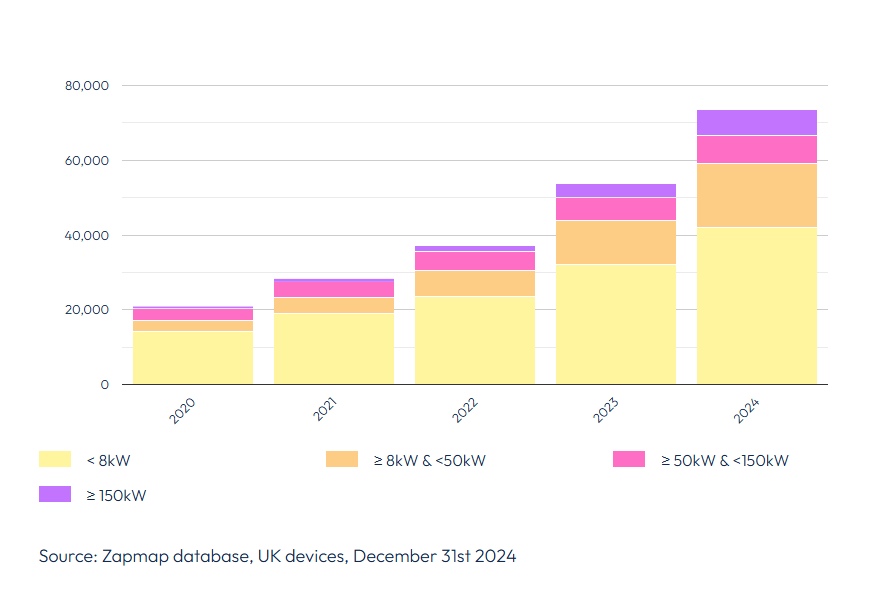

The shorter range of EVs compared to ICE vehicles is a significant issue for many people who take their cars on longer journeys. There is the phenomenon of range anxiety when the battery charge level falls below 10% and drivers become fearful about running out of charge. This is compounded by the lack of availability of public EV charging points which are in working order – although the situation is improving. The number of public charging points has grown at a steady rate over the years and there are currently more than 70000 in the UK.

With our current battery technology, it is not possible to increase the range of a small car, like the electric Vauxhall Astra, to match the range of the equivalent petrol model. To achieve a range of 500 miles the battery capacity would have to be around 150 kWh. Such a battery would be too large and heavy to be practical.

When it comes to range, the driver of an ICE vehicle has another advantage over an EV driver. They can easily and cheaply extend its range by carrying extra fuel in a Jerry Can.

This 10 litre Jerry Can be bought at modest cost and extends the range of the petrol Vauxhall Astra by over 100 miles. Source https://www.jerrycans.co.uk/product-category/plastic-fuel-cans/10-litre-plastic-fuel-cans/

This is not an option for EVs. It is strongly not recommended to connect a spare battery to an EV to extend its range and would almost certainly invalidate the manufacturer’s warranty. (https://electriccarwiki.com/adding-extra-battery-to-electric-car/)

On the other hand, it is worth making the point that limited range isn’t an issue for everyone who owns an EV. For someone who can charge at home, only uses their car for short journeys, and therefore doesn’t need to use public charging it isn’t a problem.

Issue: the high Costs of Public Charging

For people who can charge their EV at home the costs per mile are considerably cheaper than a petrol or diesel engine vehicle. For example, the electric Vauxhall Astra on average achieves around 3.5 miles per kilowatt-hour. For a customer who gets their electricity on the UK standard variable tariff and pays the standard rate of 25 pence ($0.31) per kilowatt-hour, the fuel costs work out at about 7.1 pence ($0.089) per mile.

At the time of writing a number of UK power companies are offering special EV charging deals where customers can charge overnight (normally between the hours of midnight and 5 AM) for as little as 7 pence ($0.0875) per kilowatt-hour. The fuel costs are then as little as 2 pence ($0.025) per mile. However, with these deals customers will usually pay more than the standard rate for their daytime use of electricity.

In comparison, assuming 46 miles per gallon and petrol costs of £ 1.40 per litre (£ 6.36 per gallon) the fuel costs of the petrol Astra work out at 13.8 pence ($0.173) per mile. So, for someone who can charge at home the fuel costs of the electric Astra are considerably cheaper. However, the upfront cost of the installation of the home charger needs to be factored in. A seven kilowatt charger currently costs £ 1100 ($1375) to buy and install (source https://electriccarguide.co.uk/how-much-does-ev-charger-installation-cost/ )

Around 30% of the UK population do not have access to home charging. They may live in a flat or in a house where a home charger cannot be installed. If they have an EV, they must use the more expensive public charging points.

The current average cost of slower/cheaper chargers, which charge at a rate of less than 50 kilowatts, is 53 pence ($0.66) per kilowatt-hour. Faster chargers, which charge at a rate of 50 kilowatts or more, average 81 pence ($1.01) per kilowatt-hour.

Taken from https://www.zap-map.com/ev-stats/charging-price-index

Using slower/cheaper public chargers, the fuel costs of the electric Vauxhall Astra are on average 15.1 pence ($0.19) per mile. This is 1.3 pence per mile more than the petrol Astra. Using faster public chargers, the fuel costs of the electric Vauxhall Astra are 23.1 pence ($0.289) per mile. 9.3 pence more than the petrol Astra.

Over a year assuming a mileage of 10000 miles, an electric Astra driver who did all their charging at slower/cheaper public chargers would pay

- at least £800 ($1000) more in fuel costs than someone who did all their charging at home and

- £130 more than the driver of a petrol Astra.

In reality, this is an over-simplification. Most drivers of EVs even if they can charge at home will undertake some longer journeys where they need to use public charging points. Even so there is a huge divide in the running costs of EVs between the haves who can charge at home and the have nots who cannot..

To address this issue, there must be a reduction in the costs of using public chargers to bring them closer in line with charging at home. The rate of tax (VAT) on electricity consumed at public chargers is 20%, whereas on domestic consumption it is only 5%. So, one thing the government could consider is to make the two rates the same.

In my next post I’ll discuss some more of the challenges the UK will face as it phases out the ICE and moves to electric vehicles.

Other Related Posts

I hope you have enjoyed this post. It is part of series of five(listed below) about the transition to zero emission vehicles and some of the challenges it poses.

- Understanding why we are shifting away from the internal combustion engine.

- The limited range of electric vehicles and the relatively high cost of public charging.

- Lack of available of public charging and the relatively long time it takes to charge an EV battery.

- Some of the challenges of EV battery technology and their high cost.

- Could hydrogen-powered vehicles be an alternative to electricvehicles?

Also, if you’ve not done so already, please take a look at the Explaining Science YouTube Channel.

The popular astronomy playlist may be of particular interest to those of you without a strong scientific background.

marvelous! Robot Teachers Assist in Overcrowded Classrooms 2025 optimal

LikeLike

Good balanced article that. I think we agree on most things. Certainly about the awful pricing of away from home charging.

On my own deal from Audi, they installed an Ohme tethered charger as part of the purchase deal – even though the car bought was second hand. And yes, i am one of the lucky ones who can charge at home and who also has Solar PV for much of my daytime electricity provision which i’m hoping will offset the slight increase in my daytime rate (2p per kWh).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes,

I think to reinterate a previous reply..

One of the biggest issues is the big gap between the price of at home charging and public charging where it’s an average of 53 pence per kWh. If you take into account the fact that roughly 1/3 of household in the UK cannot charge at home then it’s like for petrol cars the petrol car, that there existed two distinct networks of filling stations and that 1/3 of the population could only use the network of filling stations which charged twice the price of the filling stations used by the other 2/3 of the population.

This is something which needs to be addressed

LikeLike

You are right, and I am sure that prices will fall over time. It is early days yet, and public chargers are being added to the network at a fast pace. Prices are bound to fall, and if they don’t the government will need to step in at some point to ensure affordability. However, at this time, higher pricing probably provides a much needed incentive for companies to fund the installation costs of the chargers.

LikeLike

Thanks Steve: you pack a lot of useful information into a limited space – and ‘real-life’ data too; not the maker’s idealized figures for an unrealistic situation.

Some readers will have misgivings about ‘ultra-rapid’ chargers. They’ll recall that the manufacturers of coventional (non-EV) batteries, quote a maximum advisable charge-rate. (The battery makers don’t say, but the implication is that to exceed that current risks causing damage).

Some of the available EV chargers will do an (almost complete) charge in a few minutes & skeptical users will wonder how long a modestly sized battery will survive such treatment.

LikeLike

Thank you David for some interesting observations

LikeLike

I think that most of these facts and figures are correct, except that the advice to not charge to more than 80% capacity applies only to rapid chargers. For home charging, it would be normal to charge to 100% each day, which extends the range somewhat. Nevertheless, owning an electric car requires a change in behaviour: instead of filling up the tank once a week, you simply plug the car in each night. So for most people, the range is not a limitation except when undertaking infrequent long journeys. Besides, battery technology is improving year by year. My own car (MG4 Trophy, Extended Range) cost me £33,000 and has a battery capacity of 77 kWh, making it a better choice than the Astra. Even larger batteries are available from brands like Tesla, Peugeot, Mercedes and others. Having said that, you are right to identify the public charging network as the weakest link in the transition.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment,

To me one of the biggest “unfairnesses” is the big gap between the price of at home charging where it can ccost as little as 2 pence per kWh if you’re on a “EV special tariff” and public charging where it’s an average of 53 pence per kWh. If you take into account the fact that roughly 1/3 of household in the UK cannot charge at home then it’s like, if you take the example of the petrol car, that there existed two distinct networks of filling stations and that 1/3 of the population could only use the network of filling stations which charged twice the price of the filling stations used by the other 2/3.

This is something that needs to be addressed.

LikeLiked by 1 person