Revised 25 November 2025

In what is a departure from my usual topics of astronomy and space science, I’ve written a series of posts on the transition to zero emission vehicles. This is part of thegeneral movement worldwide to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In this post I will talk about hydrogen-powered vehicles which have been proposed as an alternative to electric vehicles. Although as I’ll explain later hydrogen vehicles certainly aren’t zero emission if we take into account the way hydrogen is generated.

Hydrogen Powered Vehicles

Hydrogen-powered vehicles have fuel cells which consume hydrogen and oxygen, from the air, to produce electricity. The electricity is then used to run an electric motor which powers the vehicle. The energy flow around a hydrogen-powered vehicle is shown below.

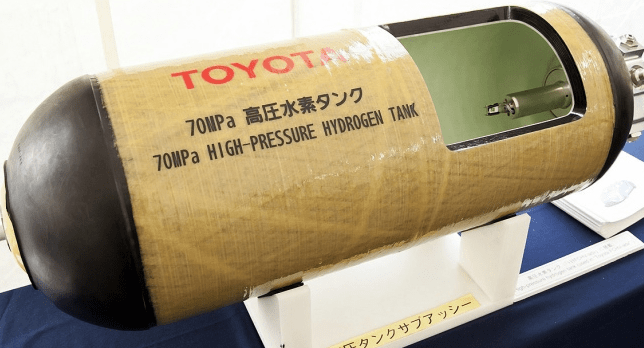

The hydrogen tank stores hydrogen gas at a very high pressure – around 700 times atmospheric pressure. Within the fuel cell, the hydrogen reacts with oxygen from the air to produce electricity with water as the by-product. The process is roughly 50% efficient.

The electricity charges a small lithium-ion battery which feeds the electric motor which powers the vehicle. Like EVs, hydrogen-powered vehicles also have mechanisms to recover the kinetic energy lost when they decelerate or break.

The lithium-ion buffer battery is much smaller (and thus lighter and cheaper) than the battery in an EV and will typically hold 2 kWh of energy.

Hydrogen-powered vehicles don’t need a long time to refuel. The pump at a hydrogen filling station looks much like a petrol or diesel pump and refuelling typically takes about five minutes – a much shorter time than it takes to fill an EV.

Hydrogen has the highest energy density (when expressed as energy per unit mass) of any chemical fuel. When combined with oxygen to produce water, one kilogram of hydrogen releases 39.5 kilowatt-hours of energy. This is 3.2 times the amount from one kilogram of petrol.

One drawback of hydrogen is that it is a difficult to substance to handle. At atmospheric pressure, it boils at -252.9 oC and cannot be compressed into a liquid at temperatures above -240 oC. It is impractical for a vehicle to have a refrigerated fuel tank operating at such extremely low temperatures. This is why hydrogen must be stored as a highly compressed gas.

Hydrogen Powered Cars For Sale in the UK

At the moment, the only hydrogen-powered car on sale in the UK is the Toyota Mirai (named after the Japanese word for future). It retails at £65000 ($81 000).

Its range is around 400 miles on a full tank of 5.6 kg of hydrogen. Hydrogen is the least dense element in the period table and, even when compressed to 700 times atmospheric pressure, one kilogram of hydrogen has a volume of 23.5 litres at room temperature. So, the Mirai’s fuel tanks need to be large. It has three hydrogen tanks with a total capacity of 142 litres (31 gallons). The tanks need to have thick walls to withstand the high pressures.

Hydrogen Powered Vehicles Where to Fill Up

To put it mildly, the take up of hydrogen- powered vehicles has been slow in the UK. There are estimated to be only 200 on the nation’s roads. A massive obstacle is that the hydrogen network is very limited. There are only 7 filling stations in the whole country. This makes owning a hydrogen-powered vehicle a complete non-starter for most people. Although it might work if you lived close to a hydrogen filling station and didn’t go on long journeys where you were likely to run out of hydrogen with no filling station nearby. It certainly wouldn’t work for me; I’d have to drive 60 miles to fill up!

In the UK, hydrogen currently costs around £12 per kilogram [1]. At this price, it would cost £67 to fill up the Mirai. The fuel costs work out at 17 pence ($0.21) per mile, which is more than an ICE engined car.

Is Hydrogen a Green Fuel?

Although a hydrogen powered vehicle only emits water as its waste product, it cannot be considered as a green fuel. If we look at the entire cycle including generating the hydrogen, running a hydrogen-powered car releases a great deal of carbon dioxide. Globally most hydrogen is generated by a process called steam methane reforming. The overall chemical reaction is summarised below. Essentially, methane (the main component of natural gas) and steam are heated up to a temperature of 800 to 900 degrees Celsius and react to produce hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

CH4 + 2H20 + energy –> 4H2 + CO2

Methane + steam + heat –> hydrogen + carbon dioxide

The reaction is what chemists call an endothermic reaction. It requires a lot of heat to be added to keep it going. For every one kilogram of hydrogen produced this way, 5.5 kilograms of carbon dioxide are generated. The carbon dioxide is normally released into the atmosphere – contributing to global warming. If the heat needed to keep the reaction going is generated by burning fossil fuels, then even more carbon dioxide is generated.

As an alternative to using methane, coal can be used. In this case, for one kilogram of hydrogen produced 11 kilograms of carbon dioxide are generated!

Hydrogen can also be produced by passing an electric current through water – splitting it into its components hydrogen and oxygen.

2H20 + energy –> 2H2 + O2

Water + electricity –> hydrogen + oxygen

This is the reverse reaction to the one that happens in the fuel cell. It produces no carbon dioxide in the overall process, provided the electricity has been generated in a green way (e.g. wind, solar or hydroelectricity). If this is the case, then the hydrogen is called green hydrogen. Green Hydrogen is on average three times more expensive than hydrogen produced by steam methane reforming which is known as grey hydrogen.

Because of its high cost, only 1% of the hydrogen produced globally is green hydrogen [2}. Most hydrogen is grey hydrogen using the SMR process outlined earlier. There is also blue hydrogen where the carbon dioxide produced is captured and stored underground.

Other Related Posts

I hope you have enjoyed this post. It is part of series of five (listed below) about the transition to zero emission vehicles and some of the challenges it poses.

- Understanding why we are shifting away from the internal combustion engine.

- The limited range of electric vehicles and the relatively high cost of public charging.

- Lack of available of public charging and the relatively long time it takes to charge an EV battery.

- Some of the challenges of EV battery technology and their high cost.

- Could hydrogen-powered vehicles be an alternative to electricvehicles?

Also, if you’ve not done so already, please take a look at the Explaining Science YouTube Channel

The popular astronomy playlist may be of particular interest to those of you without a strong scientific background.

References

[1] https://www.autotrader.co.uk/content/advice/hydrogen-fuel-cell-cars-overview (Accessed 23 November 2025)

[2] IRENA (2022). Hydrogen. [online] http://www.irena.org. Available at: https://www.irena.org/Energy-Transition/Technology/Hydrogen.(Accessed 23 November 2025)

I have a nephew who thinks hydrogen powered vehicles are the future. Thanks for filling in the various details. Interesting technology. Getting the infrastructure in place will be a challenge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes here in the UK the infrastucture to generate and distribute hydrogen is pretty much non-existant. This makes owning a hydrogen fuel celled car impractical for most peope

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your nephew may be on to something.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Its amazing concept, for more energy efficient vehicles and also, very much feasible, its implementation is already there? Quite useful concepts of hydrocarbons in real life application

LikeLike

Hi Steve,

A remarkably informative & easy-to-read series of articles. Well done!

One thing that occurs to me — although it doesn’t have a very logical basis: tank pressures of ca. 700 bar …. Of course the tank will have been designed & tested to perform adequately.

The commonly-used pressure in cylinders for laboratory or industrial use is 200 bar (or in special cases, 300 bar), and even those are treated with respect.

I’d guess that quite a few owners will suffer significant anxiety, whether it’s justified or not, at being trapped – sorry, confined – next to a large amount of highly flammable gas under such pressure.

Still, I’m sure that the makers of the airship – er sorry I meant the vehicle – will hasten to reassure them!

Regards, David.

LikeLike

An interesting point. The reason why the tank has to be so highly pressurised is of course to reduce the volume of the hydrogen tank. To store 5.6 kg of hydrogen At a pressure of (only!) 200 bars wold need an array of fuel tanks with a total capacity of around 500 litres (110 British gallons) which would take up far too much space.

LikeLike

Thank you for this article. I’ve been concerned about the “hydrogen” car issue for a while. First issue: infrastructure – Right now, you can drive across America, and not in big cities – not in little cities – but in the middle of nowhere, are dozens of e-vehicle charging stations. The infrastructure bill that was in the billions of dollars for these – was sorely wasted. Worse, it was wasted on class 2 charges, which is still a slow charge. The problems the utilities had, that nobody knew about, was that the charging stations put an undue amount of stress on the grid in locations where the grid was built for home and business – not this added burden. It creates an unpredictable load and the utilities (due to some poor, corrupt and greedy long-term decisions by utilities), are simply not able to support it.

Then, we had the issue of not having the infrastructure. Power lines don’t just run everywhere 100% – so upgrading this for evehicle stations was a massive and large expenditure on taxpayers with very little to show for it. So – why would this be different for hydrogen? A) hydrogen embrittles a LOT of metals – destroying them over time. Not only will taxpayers be spending 100s of billions to install hydrogen charging stations for a few cars – but those lines constantly need replaced. B) the leak detection for faults in these lines is EXTREMELY difficult to sustain, manage, and WILL lead to undetected faults. The predictable outcome is – explosions and fires, whether in the middle of a city or the middle of the countryside – this will be an issue. And, for folks who don’t know, underground lines are hit ALL the time – and that will be a spark and an explosion on a pressurized lines and lives will be lost. I have to deal with this all the time – in locations where contractors use state-of-the-art equipment, even. (then there is ventilation, temperature control, soil & groundwater contamination, maintenance and access – and the mile long list of every reason NOT to install hydrogen).

Second issue is the hydrogen itself. Do people understand the amount of hydrogen we would consume? We are talking billions of vehicles on the road – every day (hundreds of millions in the US, alone) – and the most stable and safe source of hydrogen is from water. I’m not prepared to put our water supplies on the line for “fuel consumption”. We can risk a lot of resources – but not water. Of course – there is gasification through natural gas or coal. But – those are fossil fuels and as you pointed out, not very “Green” friendly. Gasification through biomass – but that would be a LOT of food crops – like more than anyone could comprehend, and would come with a huge amount of non green friendly outcomes. And, in all these technologies, once you account for the massively inefficient processes, losses, infrastructure erosion, and so on – the outcome is worse than any climate change prediction.

For me, it comes down to this: oil is sustainable, for a VERY long time. Do we need less carbon emissions/ Sure. But – we waste a LOT of money chasing irrational ideas for those profiteers abusing it, than we do actually formulating solutions. The combustion engine has been upgraded a LOT – but there is still a LOT of room for growth. The conversion efficiencies of oil and natural gas have a LOT of room for growth. And, there may yet be another solution. The problem is, when money is wasted on trying to bring to market an idea that has so many red flags and flaws, it’s wasting valuable funds that could be used on actual solutions.

LikeLike

Thank you for you interesting and well thought out comment. At the moment in the UK, replacing the ICE with hydrogen fuel cell vehicles is a complete non starter. There is just no infrastructure to support it. Due to limited demnand, the number of hydrogen filling stations (seven in the entire country!!) hasn’t changed over the last decade.

Another point is that To me intuitively it feels dangerous to be in a vehicle with 140 of litres of hydrogen compressed 700 bars. However, I haven’t done any research on on either the risks or the impacts of hydrogen tanks rupturing in an accident.

LikeLiked by 1 person