Updated 16 January 2016

The Oort cloud is theorised to be a vast cloud of icy bodies beyond the boundary of the Solar System. It was proposed by the Dutch astronomer Jan Oort back in 1950. Interestingly, the Estonian astronomer Ernst Opik had published a very similar idea in 1931. However, Opik’s earlier work was largely ignored and today we call this structure the Oort cloud.

The Outer Solar System

Before looking at the Oort Cloud it is worth first considering the outer Solar System.

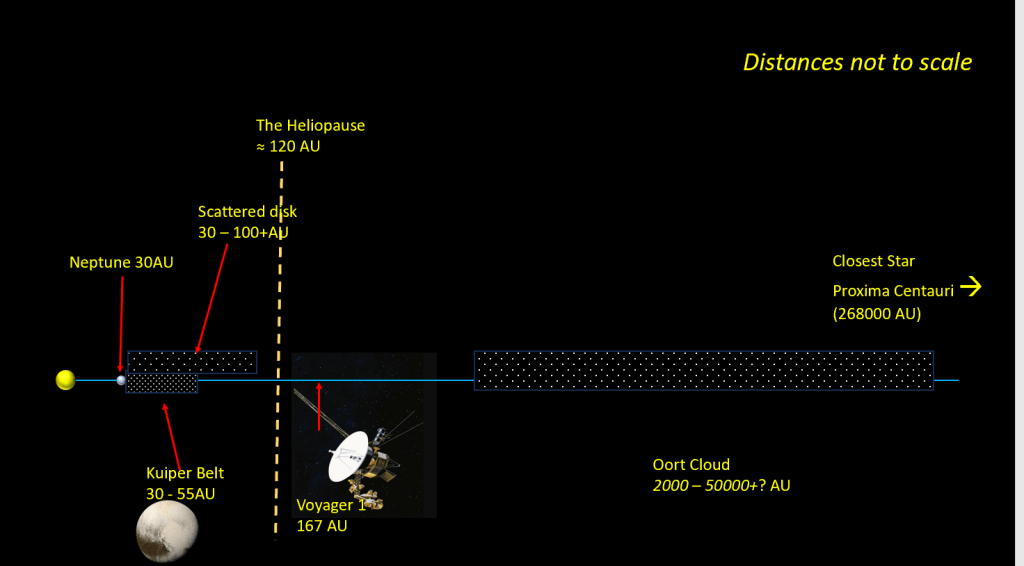

Neptune is the most distant planet from the Sun, lying 30 astronomical units away, where one astronomical unit (AU) is the average distance between the Earth and the Sun. Beyond Neptune at a distance of 30 to 55 AU is the Kuiper belt of small icy objects. The best known Kuiper belt object is the dwarf planet Pluto. The scattered disc from 30 to 100 AU is an extension of the Kuiper belt and includes objects moving in orbits with greater eccentricities, meaning they’re in more elliptical orbits, and also further above and below the ecliptic plane (the plane in which the Earth orbits the Sun) than traditional Kuiper beltobjects.

The heliopause is the boundary between the Solar System and the diffuse gas and dust which lies between stars known as the interstellar medium. NASA’s Voyager One spacecraft launched back in 1977 to study the outer planets Jupiter and Saturn is the most distant human made object. It is now at a distance of 167 AU from the Sun and is travelling away at the rate of 3.57 AU per year -all the time its speed being gradually slowed by the pull of the Sun’s gravity.

The Oort Cloud is believed to lie from 2000 to at least 50 000 AU from the Sun, with some estimates putting its outer boundary as high as 100 000 AU. In hundreds of years’ time Voyager One will reach the Oort Cloud, but by this time its transmitters will no longer be working. So we won’t know what it uncovers.

Structure of the Oort Cloud.

The Oort cloud consists of two parts

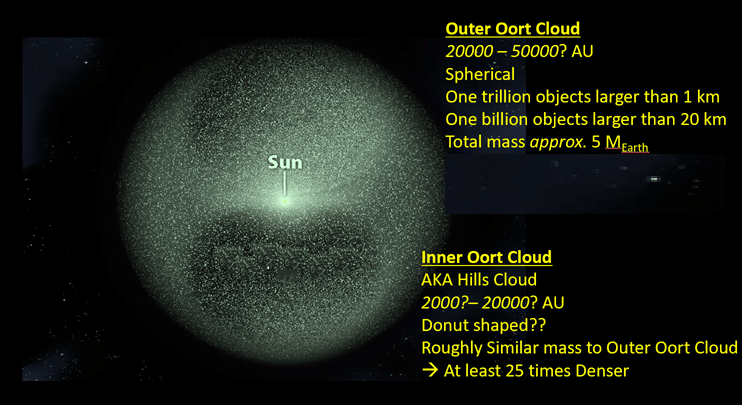

The outer Oort cloud is roughly spherical and has around a trillion objects larger than a kilometre in diameter and around a billion objects larger than 20 kilometres in diameter. Its total mass is approximately five times the mass of the Earth. But when you do the mathematics, it’s not very dense at all. Averaged out, if you took a volume of one thousand cubic astronomical units it would have only two objects larger than 1 kilometre in diameter.

The inner Oort cloud which is sometimes known as the Hills cloud is doughnut-shaped and, although its mass isn’t accurately known, is likely have at least the same mass as the outer Oort cloud -possibly 2-5 times greater. So, because of its smaller volume, it must be at least 25 times denser.

Brightness of objects in the Oort Cloud

- The intensity of sunlight hitting an object declines as the inverse square of its distance from the Sun (the well-known inverse square law)

- The intensity of the light reflected back and viewed from the Earth declines as the inverse square of its distance from Earth.

So, when you put the two together, you have an inverse fourth power relationship. The great distances and this inverse fourth power relationship mean that objects in the Oort cloud are incredibly faint.

Astronomers measure the brightness of objects on the magnitude scale . The larger the magnitude value the fainter the object. If we assume that it reflects 35% of the light hitting it, an object at a distance of 2000 AU one kilometre in diameter would have a magnitude of +49. This is 250 million times fainter than the faintest objects which can be detected with Earth-based telescopes.

If we consider a much larger object 20 km in diameter, at a distance of 2000 AU, this would have a magnitude of +42.5. This is 630 000 times fainter than the faintest objects which can be detected with Earth-based telescopes.

The conclusion is clear…..

No Oort cloud objects have ever been seen or can be seen with our current technology.

So, the natural question to ask, is how do we know the Oort cloud exists?

Evidence for the Oort Cloud

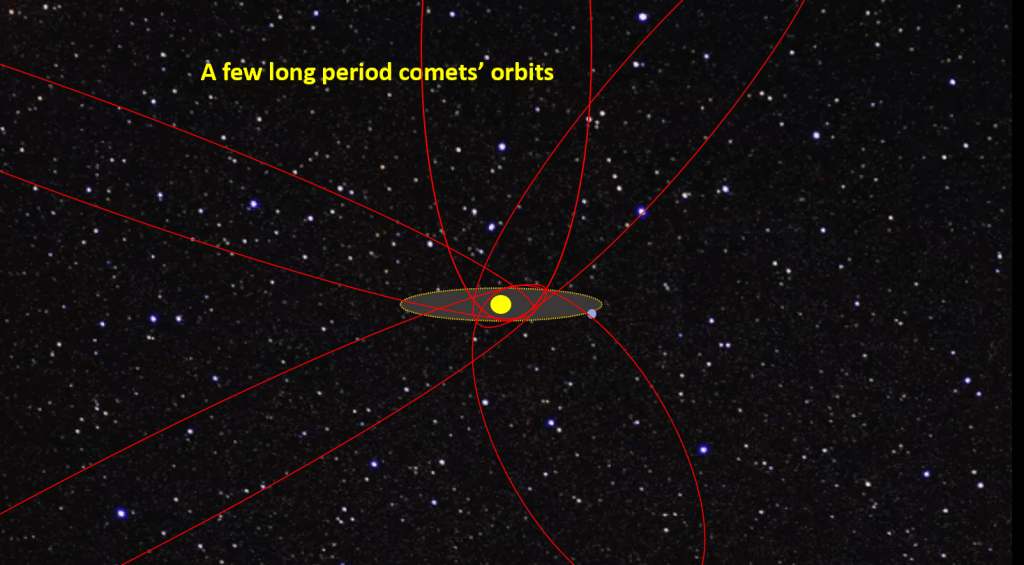

Short period comets tend to be in orbits which lie relatively close to the plane of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun – the ecliptic. Long period comets aren’t constrained to be in the plane of the ecliptic. Their orbits can take them well above and below the ecliptic They can orbit the Sun in the same direction that the Earth does or in the opposite direction. Their aphelia (the point in their orbitswhen they’re furthest from the Sun) lie thousands of astronomical units from the Sun and when you plot the aphelia of all long period comets it is spherical in shape.

The theory is that there must be a near spherical cloud of icy bodies around the Solar System which provide the source of these comets

An object in the outer region of the Oort Cloud is very weakly bound to the Sun. At a distance of 50 000 AU it takes 11.2 million years to complete one orbit. The Sun’s gravity at this distance is two and half billion times weaker than it is at the Earth’s distance from the Sun. The galactic tide or a passing star can disrupt this cloud deflecting bodies into the inner Solar System or expelling them from the Sun’s gravitational influence altogether.

What is the Galactic tide?

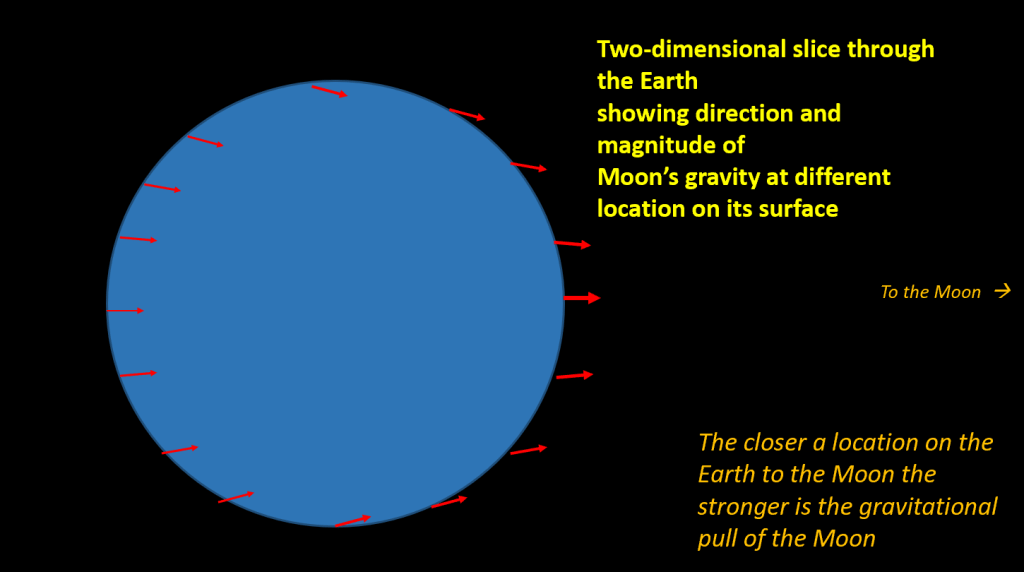

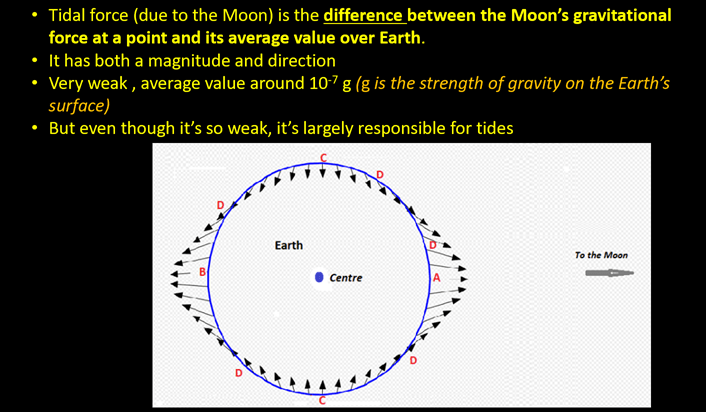

Most people are familiar with the tides caused by the Moon. This is due to the fact that the average strength of the Moon’s gravity is different on the side of the Earth facing the Moon than on the side facing away. In fact, not only does the pull of the Moon’s gravity vary in strength it also varies in direction.

The tidal force is the difference between the Moon’s gravity at a location and its average value over the entire Earth. As shown below, it has both a magnitude and direction. It is a very weak force – having a strength about 10 million times weaker than the Earth’s gravity. But even though it is weak it is the force largely responsible for tides, the raising and lowering of the sea level twice a day.

The Solar System lies in the outer region of our Milky Way galaxy about 27 000 light years from the galactic centre. If we look at the Oort cloud, the side furthest away from the galactic centre experiences a weaker gravitational attraction than the side closest. So there is a tidal force on the Oort Cloud.

However, not all the mass is concentrated at the galactic centre. A lot of matter resides in the galactic disk and the galaxy is surrounded by a dark matter halo. These concentrations of mass also contribute to the galactic tide – making it quite complicated. The video at the end of this post describes it further.

Although the main evidence for the Oort cloud is the need to explain the origin of long period comets with their aphelia having a near spherical distribution thousands of AU away from the Sun, there are other good reasons why the Oort Cloud should exist. Another strong piece of evidence is that models of the evolution of the Solar System predict that, early in its history, interactions with the giant planet scattered a significant amount of icy bodies to its outer edges. Computer simulations predict that these would have been flung out into extremely remote orbits. The slow and steady action of the galactic tide would have gradually altered these orbits, from all of them being entirely in the ecliptic plane, into a more spherical distribution.

The Hills Cloud

The Hills cloud, or inner Oort cloud, is a more recent development to the theory, first proposed by Jack Hills back in 1981. Rather than being spherical, it is believed to be doughnut-shaped having an Inner radius of 2,000 AU and an outer radius of 20,000 AU. Because of its smaller volume the density of icy bodies must be much higher. Although there is no direct observational evidence for it, recent computer simulations have shown that such a structure should form inside the main Oort Cloud. However, just to complicate matters further, a paper written in 2025 [1] suggested that the Hills cloud isn’t doughnut-shaped and could have a spiral structure.

Because the outer Oort cloud is sparsely populated, and its objects are subject to gravitational perturbations from passing stars and galactic tides which can lead to them escaping from the Sun’s gravitational influence altogether, the Hills cloud may work as an icy body reservoir that continuously supplies objects to the outer Oort cloud, maintaining its population over billions of years.

Passage of Gliese 710 Through the Oort Cloud

In around 1.3 million years time, the star Gliese 710 will plough through the Oort cloud at a velocity of 14.5 km/s, as it does so it will cause significant disturbance. Over a period of a few million years this will send showers of comets to the inner solar system. To find out more view my post on the close approach of Gliese 710.

And finally…

I hope you have enjoyed this post. I have made a video about the Oort cloud which is available on my the Explaining Science YouTube channel.

References

[1] Nesvorny, D., Dones, L., Vokrouhlicky, D., Levison, H.F., Beauge, C., Faherty, J., Emmart, C. and Parker, J.P. (2025). A Spiral Structure in the Inner Oort Cloud. [online] arXiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.11252 [Accessed 15 Jan. 2026].

A very interesting post and video explaining the mysterious Oort Cloud, Steve. Thanks. I’ve often wondered how astronomers theorised its existence.

LikeLike

Thank you Roger and glad you found the post and video interesting

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder if the hypothetical Oepik/Oort/Hills cloud can be considered a “dark cloud” or not.

LikeLike

An interesting question 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Steve,

I suspect that even if Gliese 710 doesn’t have an Oort cloud of its own, it will capture much of “ours” on its journey.

A treat in store? (providend, as you say, that we’re still around to observe it). Until a few years ago we could have been reasonably sanguine about that — now there’s more room for doubt. Still, we musn’t let considerations of politics or human behavior intrude into a scientific discussion must we.

David.

LikeLike

Thanks.. Pity we we won’t be around to see the close approach of Gliese 710 🙂

LikeLike