Revised 18 December 2025

We’re all familiar with specifying a location by its latitude and longitude, but I thought it would be interesting to write a post about latitude and longitude on other bodies in the Solar System.

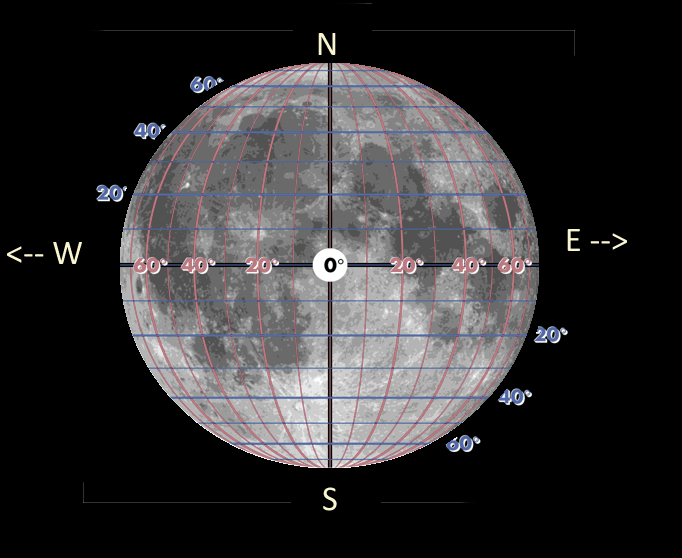

Locations on the surface of the Moon are given a latitude and longitude just like they are on Earth. The Lunar North Pole is the pole which lies above the ecliptic (the plane of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun) and the pole which appears uppermost when the Moon is viewed from the Earth’s Northern Hemisphere.

The lunar poles have latitudes of 90o south and 90o north and the lunar equator has a latitude of zero.

With longitude, on many astronomical bodies, there is no obvious line which can be assigned zero longitude – the prime meridian. The Earth’s prime meridian was defined by international agreement in 1884 as the line of longitude which passes through the Airy Transit Circle, a telescope at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London. The choice of Greenwich was somewhat arbitrary, and any other line of longitude could have been chosen. France did not vote for the zero longitude line to pass through Greenwich and for decades afterwards many French maps showed the prime meridian passing through Paris. I can recall my father having an old Larousse French encyclopaedia published in the 1950s in which all the maps were drawn this way.

Moon maps before the advent of space probes were drawn from the viewpoint of someone looking at the Moon from the Earth. So, from the early days of lunar mapping, the Moon’s prime meridian was naturally chosen to pass through the centre of the Moon’s near side.

East and west are defined in the same way as they are on Earth. Therefore, if you were standing on the Moon’s surface and facing south, east would be to your left and west to your right.

- Locations with longitudes between 90oW and 90oE are on the Moon’s near side and

- locations further west than 90oW or further east than 90oE are on the Moon’s far side.

Because of libration, which causes the Moon to appear to wobble up and down and from side to side as it moves around in its orbit, locations which are only just on the far side lying between 90oW and 98oW or between 90oE and 98oE are visible from Earth at certain points in the Moon’s orbit.

How the features which are visible on the Moon vary due to libration

East and West on the Moon.

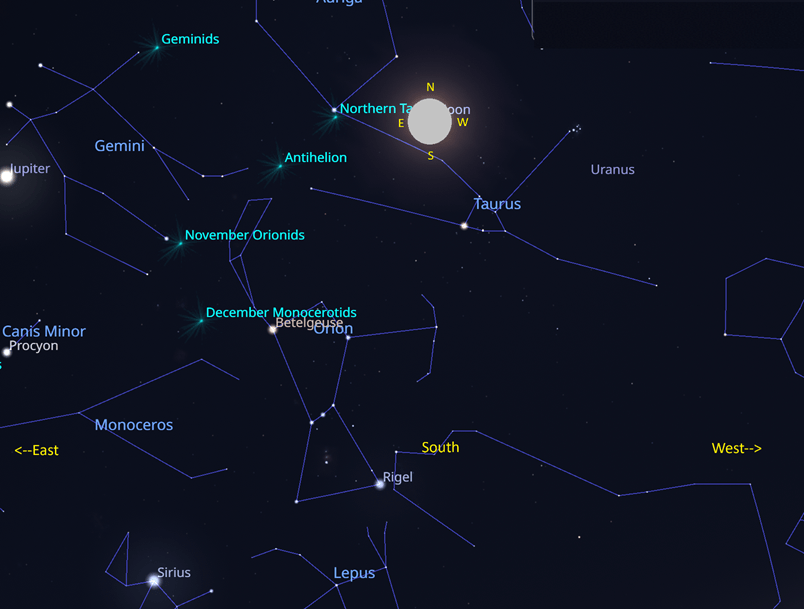

Prior to 1961 astronomers used to define east and west the other way round. The eastern edge of the Moon used to be defined as the edge in the direction that faced east when viewed from Earth and the western edge the direction that faced west.

If you are in the Northern Hemisphere and looking south, then in the old lunar coordinate system the eastern edge of the Moon will appear on its left hand side and the western edge on its right hand side.

However, in that year the International Astronomical Union (IAU) recommended that in lunar maps the direction of east and west should be reversed. This brought them into conformity with terrestrial maps. In the post 1961 definitions when north is at the top of a map east is to the right, and west is to the left, just as on Earth.

The old definitions of east and west are still reflected in the names of certain places on the Moon. There is a large sea called Mare Orientale which is Latin for “Eastern Sea”, which lies close to the near side/far side boundary and is sometimes visible on the western rim of the Moon. In the modern coordinate system, its longitude is 92.8o west.

Latitude and Longitude on the Planets in the Solar System.

With the planets, latitude, longitude and the direction of east and west are defined as on Earth. The definition of the prime meridian is set by the International Astronomical Union and is in all cases pretty arbitrary. The important thing is that astronomers agree where the line of zero longitude is; so everyone is using the same coordinate system!

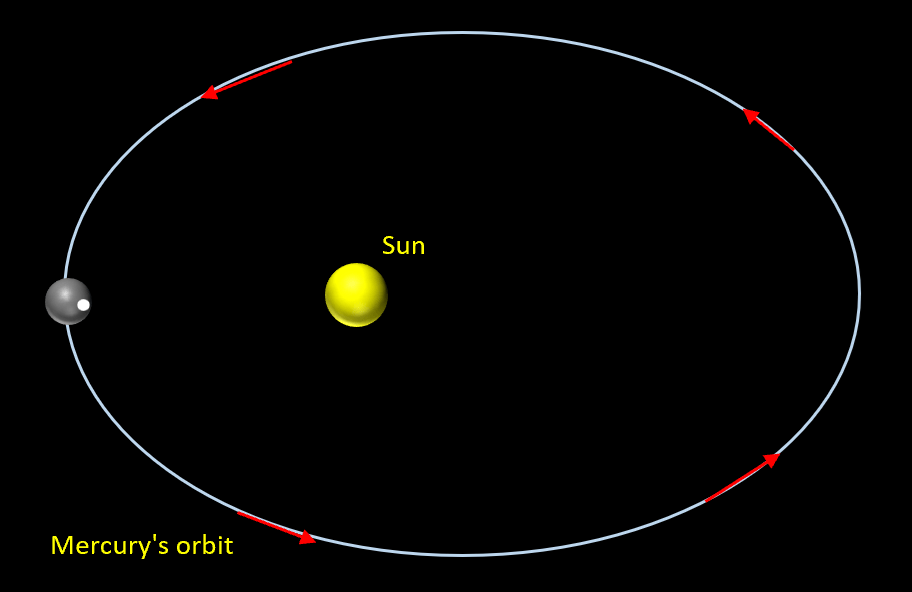

Mercury

Mercury has the most elliptical orbit of any planet. At its closest to the Sun (perihelion) it is 46 million km away and at its furthest (aphelion) is nearly 70 million km away. It takes 87.969 days to orbit the Sun, and its rotation period is locked in a 3:2 resonance. It takes 58.646 days to rotate once on its axis exactly two thirds the time for one orbit.

At perihelion Mercury is closest to the Sun. So, the Sun is bigger and brighter than at other times in its orbit. Let the white dot represent the location on its surface, known as the subsolar point, where the Sun is directly overhead at the perihelion. The subsolar point at perihelion is known as a hot pole.

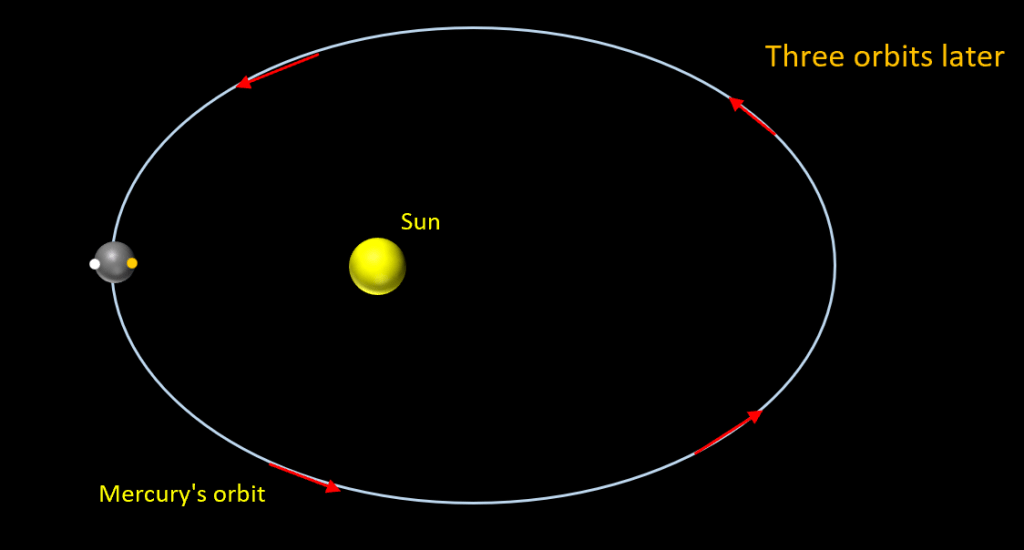

One complete orbit later, Mercury has rotated on its axis exactly one and a half times. The orange dot represents the new location (second hot pole) where the Sun is directly overhead. The original hot pole is on the directly opposite side of Mercury.

Two complete orbits later, Mercury has rotated on its axis exactly three times. The hot pole is back in its original location and the second hot pole is on the opposite side of Mercury.

Three complete orbits later, Mercury has rotated on its axis exactly four and a half times. The hot pole is back to its second location and the original hot pole is again on the opposite side of Mercury.

Because the tidal locking of Mercury’s orbit and rotation periods mean that there are only two locations on its surface where the Sun is overhead at the perihelion, the hot poles form natural candidates for defining Mercury’s prime meridian. One of these two hot poles has been arbitrarily chosen to lie on the line of zero longitude of Mercury.

Venus

Venus is surrounded permanently by thick clouds making it impossible to see any detail from Earth. Its surface has only been mapped since the late 1970s by space probes using radar. Before that there were no maps of the surface because it couldn’t be seen. The first global map of Venus was created by NASA’s Magellan mission between 1990 and 1994. This mapped 98% of the planet’s surface with a resolution of 120 metres.

In 1992 the IAU defined that the prime meridian passes through the central peak located within a crater called Ariadne. This choice of prime meridian was arbitrary, and any other feature could have been chosen.

Mars

Mars has a thin atmosphere and surface features have been observed on the planet since the seventeenth century. As astronomers began to catalogue these features, it became necessary to have a coordinate system.

Following extensive mapping of the surface of Mars by the Mariner 9 spacecraft in 1971 and 1972, it was proposed that the Martian prime meridian would pass through a small crater called Airy-0. This proposal was adopted by the IAU.

Interestingly, the German astronomers Wilhelm Beer and Johann Heinrich Mädler back in 1830 used observations of a clearly visible dark patch to estimate Mars’ rotation. Italian astronomer G. V. Schiaparelli used this feature as the zero longitude line on his 1877 maps. This feature later named Sinus Meridiani aligns closely to the current prime meridian.

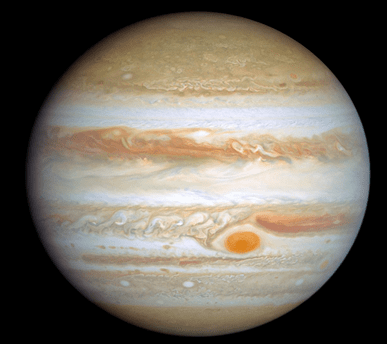

Jupiter

Jupiter is a gas giant. It has a dense atmosphere thousands of kilometres thick, below this there may be a layer of liquid hydrogen compressed to immense pressures. It is only possible to view the upper regions of its atmosphere. Jupiter isn’t a solid body and the rotation period of the features we observe varies with latitude. Near the equator, the rotation period is approximately 9 hours 50 minutes, as you move away it gets longer and near the poles it is roughly 9 hours 56 minutes. Because of this differential rotation an atmospheric feature, such as the great red spot, cannot be used to define the prime meridian.

Jupiter’s magnetic field originates from the interior of the planet and, from long term observations of this magnetic field, a rotation period of 9h 55m 29.711s for the interior of the planet has been estimated.

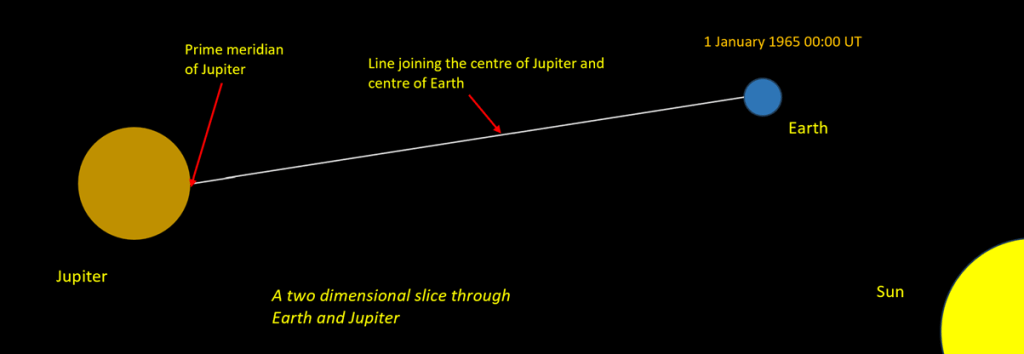

The most widely used definition of the prime meridian is known as the Jupiter System lll. In this system, zero longitude is based upon the line joining the centre of the Earth and the centre of Jupiter at 00:00:00 UT on 1 January 1965. The location of the prime meridian at a given time can be calculated by assuming the planet rotates once every 9h 55m 29.711s. (source https://lasp.colorado.edu/mop/files/2015/02/CoOrd_systems7.pdf )

Other giant planets

Like Jupiter the other giant planets (Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) don’t have a visible solid surface and are surrounded by thick atmospheres. The prime meridian is defined in a similar way to Jupiter. Namely, its position is defined for a particular date and then extrapolated to the current date by assuming a particular value for the planet’s rotation period.

Other Solar System objects

Although I have focussed on the Moon and the planets, as more Solar System objects (e.g. dwarf planets, large asteroids, the moons of planets) have been observed at higher resolutions and mapped, latitude and longitude have been defined on them as well. The general rules are as follows.

- The North Pole is the pole which lies above the ecliptic plane.

- The prime meridian is normally chosen to pass through some clearly defined location, for example a noticeable feature such as a large crater.

- However, the prime meridians of the moons of the giant planets are all defined in a different way. Their rotation is tidally locked so that one side of these moons always faces the planet, in the same way that one side of our Moon always faces the Earth. For the giant planet moons the prime meridian is defined to pass through the centre of the side facing the planet.

- East and West are in the same directions as they are on terrestrial maps.

In general, longitude is expressed on a scale from 0o to 360o degrees. So rather than saying a feature is at longitude 90o west, it is at longitude 270o.

And Finally…

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post. On the subject of the Moon, if you’ve not done so already you may wish to take a look at my e-book A Short Guide to the Moon which have revised and updated. To find out more and read a sample, without any obligation to buy, please click the link below.

I have also put together a short video if you’d like to find out more about Explaining Science

Please allow me to draw attention to Mercator’s projection which makes it possible to display compass directions as straight lines, necessary for navigation purposes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLike

Well, lots of things there I’d never even thought about! Thanks.(And this year I must remember to hunt the Perseids too….)

LikeLike

Thanks Margaret. I hope you (and your garden 🙂 ) are well. It is not a particulary good year to see the Perseids with there being an almost full Moon above the horizon but you never know you may be lucky. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂 Thanks very much, Steve. There’s a lot of basic principles in this article that I didn’t know.

LikeLike

You’re very welcome Roger. I hope you’re getting plenty of clear skies 🙂

LikeLike

Not really , Steve. It’s been Manchester weather here . . .

LikeLike

Hi Steve,

As usual, thanks for an interesting article — and one which was certainly needed, since not many of us happen to belong to the IAU !

Among your list of planets, Uranus presents quite a challenge to establishing longitude owing to its extreme axial tilt, (either slightly >90° or slightly <90° depending on which convention you follow) and hence we have to agree whether we’re seeing its N or S pole at present.

Of course one fine day, when we have a probe that can make detailed gravitational mappings, it might detect a solid surface far, far, down & thence a suitable mountain or crater (doesn’t seem very likely though does it?).

Regards, David.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks David,

You raise some interesting points.

Steve

LikeLiked by 1 person