Solar sails are the only method of spacecraft propulsion in which no fuel is needed. Until recently spacecraft powered by solar sails were the stuff of science fiction. However, following the success of the Japanese spacecraft IKAROS in 2010 the crowd-funded Light Sail 2 spacecraft in 2019 and NASA’s ACS3 in 2024, spacecraft powered by solar sails may have a role to play in future space exploration.

The Sunjammer a 1964 short story by Arthur C Clarke. It features the racing of space-yachts powered by solar sails.

How do solar sails work?

Solar sails work by using radiation pressure from sunlight to produce thrust. Effectively a solar sail is a mirror, reflecting sunlight that hits it.

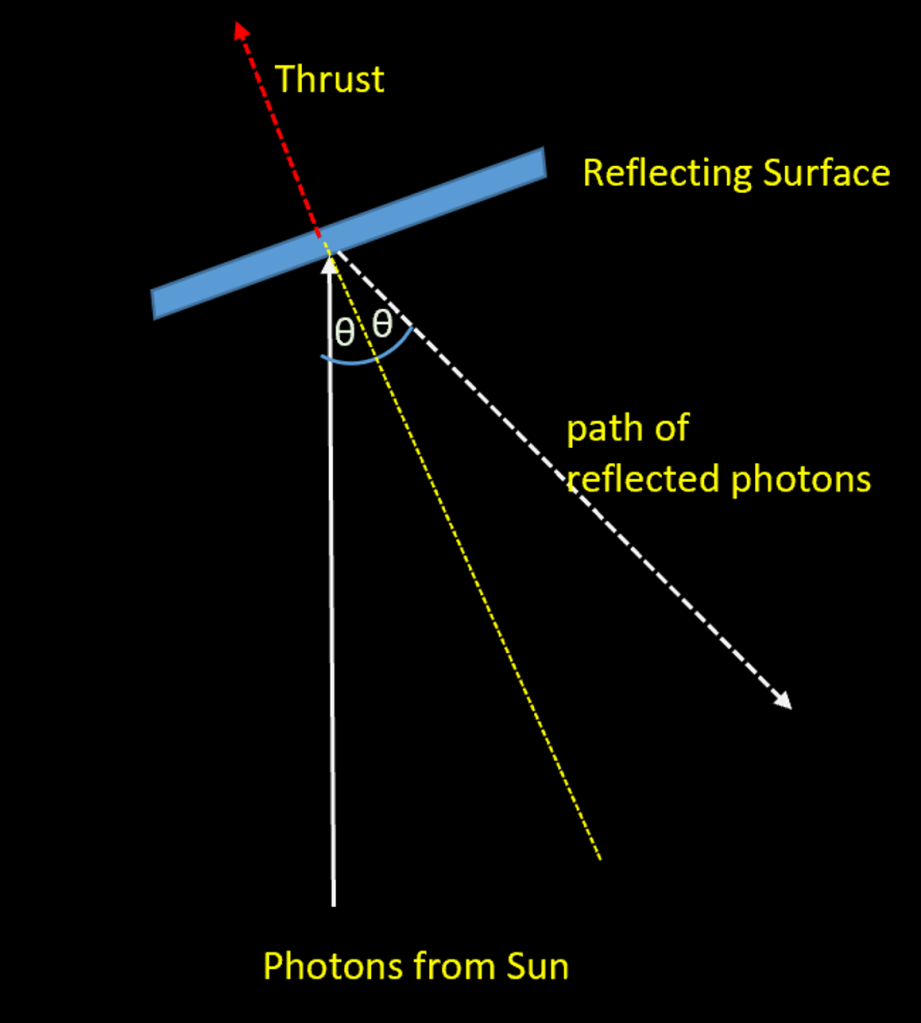

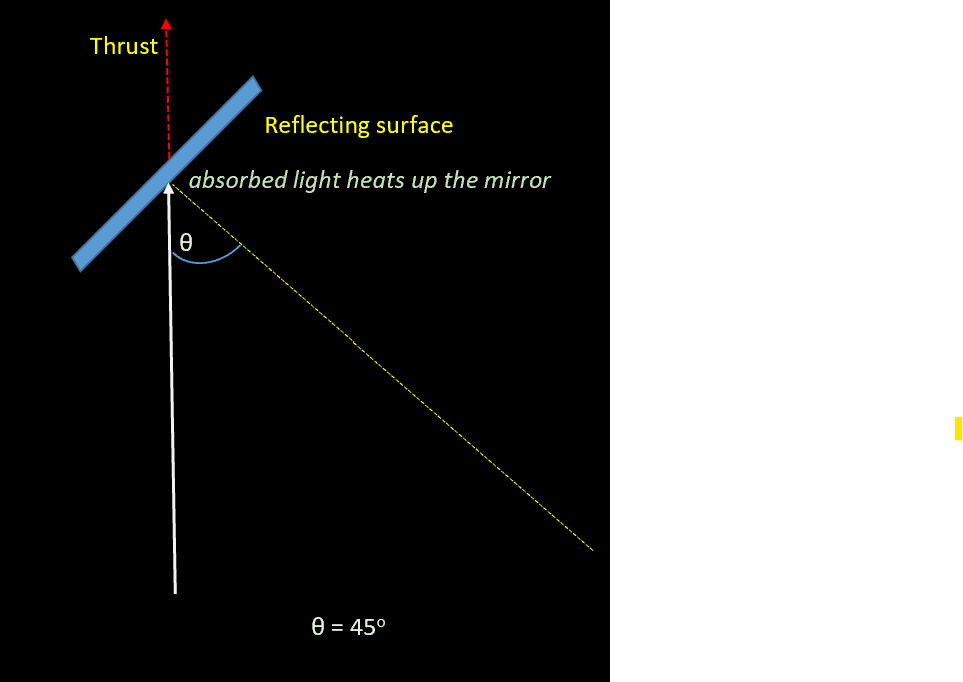

Light consists of a stream of photons, whenever a photon hits the surface of a mirror it is reflected back at the same angle it strikes the mirror, shown as the Greek letter theta (θ) above. Some of the photon’s momentum is transferred to the mirror -pushing it away in a direction at right angles to its surface. The the net effect of the vast numbers of photons in sunlight is to generate a force or thrust accelerating the mirror away from the Sun in the direction shown by the red arrow.

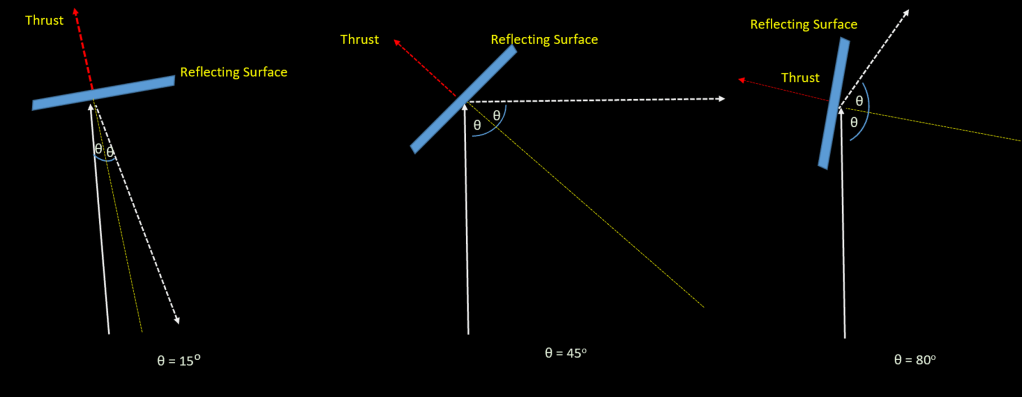

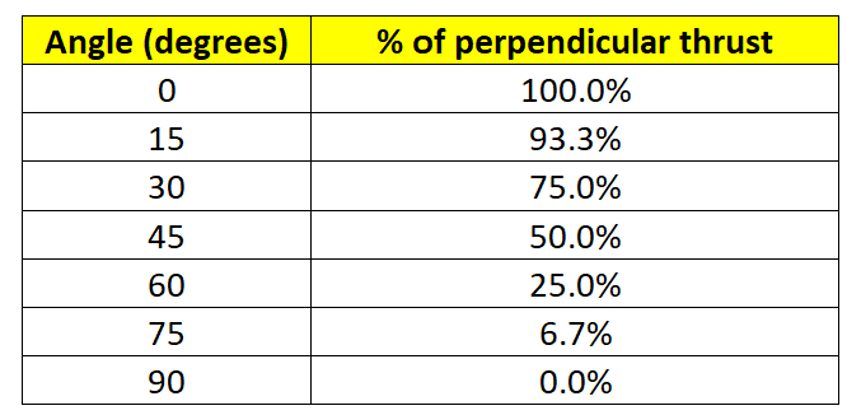

Because the direction of the thrust is always at right angles to the sail’s surface it can be changed by orientating the sail at different angles to the Sun, making it possible to steer a solar powered spacecraft.

The magnitude of the thrust varies with the sail’s orientation. It is at its greatest when the sail is perpendicular to the Sun’s direction and falls off as the angle to the Sun decreases. When the sail is edge on, i.e. at an angle of 90o to the Sun’s radiation, the thrust is zero.

In reality, no mirror is 100% efficient reflecting back every single photon that hits it. Some light is always absorbed, heating it up. Although absorbed photons also provide thrust, the maximum thrust from absorbed photons is only 50% of reflected ones

Variation with distance from the Sun

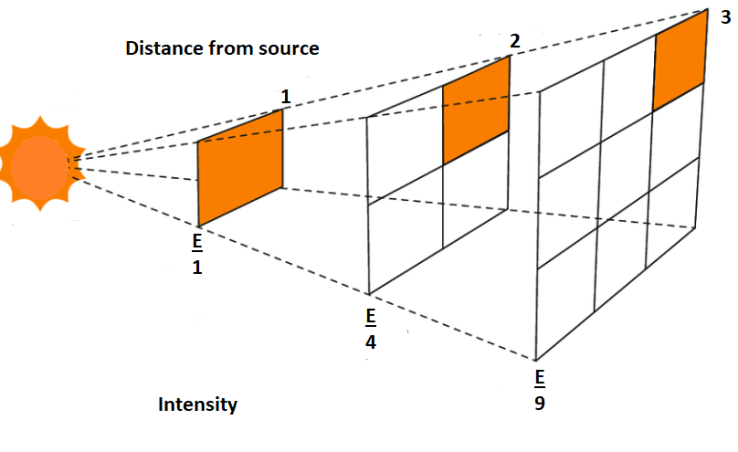

The intensity of sunlight, and therefore the thrust produced by a solar sail, falls as the inverse square of its distance from the Sun.

Using solar sails as a method of propulsion

Force is measured in newtons (for those of you in the UK and the US who and may prefer imperial units 1 newton equals 0.225 pounds force). At the Earth’s distance from the Sun, the intensity of sunlight a number known as the solar constant is 1.361 kilowatts per square metre. Assuming that:

- all sunlight is reflected, (i.e none is absorbed by the sail) and

- the sail is perpendicular to the Sun,

this value of the solar constant provides a small thrust of 0.000 009 08 newtons per square metre of sail. A 100% efficient solar sail having an area of 100 square metres would produce a maximum thrust of 0.000 908 newtons.

This is a very weak thrust compared to traditional rockets. For example, the first stage of the SpaceX Falcon 9, shown below, which lifts the spacecraft off the launchpad, produces massive 7.6 million newtons of thrust and burns for only 162 seconds before all its fuel is exhausted. The second stage, which produces 930 000 newtons of thrust, then kicks in and burns for a further 400 seconds to take the payload into orbit.

Many of you will recall from high school science

Force (i.e. thrust on the spacecraft) = mass x acceleration

So, the acceleration provided by a solar sail is the thrust divided by the total mass of the spacecraft. To maximise acceleration the thrust must be as large as possible and the mass of the spacecraft as small as possible.

A simple illustration

If we have a solar sail measuring 30 by 30 metres, giving a total area of 900 square metres and we assume that it is 90% efficient then its thrust is

900 x 0.000 009 08 x 0.9 = 0.0074 newtons

If we make the sail out of a material 0.01 mm thick having a density of 1 gram per cubic centimetre then the total mass of the sail (area x thickness x density) is

900 x 0.00001 x 1000 = 9 kg

However, in addition to the mass of the sail, the spacecraft has its own mass and there will need to be a frame to support the sail. If we assume that the total mass of the spacecraft, sail and supporting frame is 40 kg then the acceleration provided by the sail is a miniscule

0.0074 newtons/ 40kg = 0.000185 metres/second 2

However, the great beauty of solar sails is that they require no fuel. They provide a small continual acceleration in contrast to traditional rockets which provide a powerful thrust for a short time.

So, assuming there were no other forces acting on the spacecraft, over a period of one day (86 400 seconds) the spacecraft would change its velocity by:

86 400 x 0.000185 ≈ 16 metres per seconds ( which is roughly 58 km/h).

Although this is still a small change in velocity, over six months the spacecraft could increase its velocity by 10 600 km/h – without any fuel being used!

This illustrates the key feature of solar sails- they cannot produce the large thrusts needed to lift rockets off the ground, but the small constant acceleration mounts up over a period of time to produce large changes in velocity.

More concrete examples

The example I’ve given is a gross oversimplification, because it assumes that the only force acting on the spacecraft is the solar sail thrust.

In reality, things are a little more complicated.

- The spacecraft will be in orbit around the Sun, and the force of the Sun’s gravity will pull it toward the Sun. The Sun’s gravity and the spacecraft’s initial orbital parameters (distance and starting velocity) must be taken into account when calculating its trajectory.

- If the spacecraft passes another massive object, e.g. a planet, then the effect of the gravitational force due to the object will need to be taken into account.

- The thrust provided by the solar sail and the gravitational force due to the Sun are continually changing as the distance to the Sun varies.

- If the orientation of the solar sail to the Sun changes, both the magnitude and direction of the thrust will change.

Here are some example trajectories

Example 1

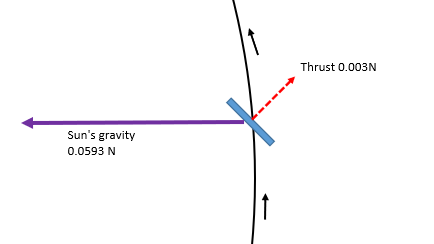

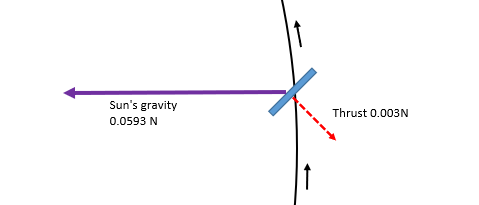

In this case, the spacecraft has a mass of 10 kg and starts off in a circular orbit at a distance of one astronomical unit (AU), which is 150 million km, from the Sun. It has a very large solar sail, inclined at an angle of 45 degrees to the direction of the Sun, which produces a thrust of 0.003 newtons.

At the initial distance of 150 million km from the Sun the force of the Sun’s gravity on a 10 kg mass is 0.0593 newtons, roughly 20 times the thrust provided by the solar sail. Interestingly, because the force of the Sun’s gravity and the intensity of sunlight both fall as the inverse square of the spacecraft’s distance from the Sun, provided the sail maintains an orientation of 45 degrees to the Sun’s direction, then the Sun’s gravity will always be twenty times larger than the thrust on the sail regardless of its distance from the Sun.

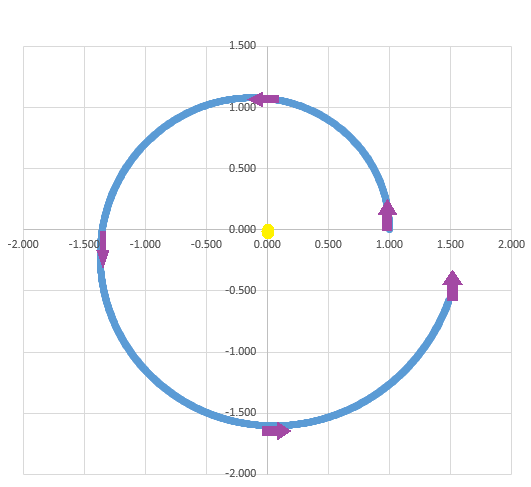

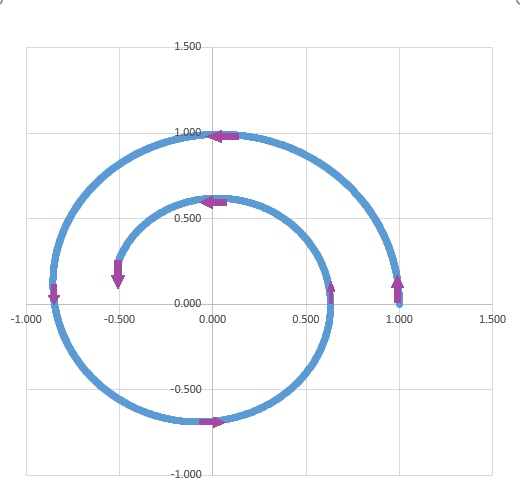

Assuming the orientation remains at 45 degrees to the direction of the Sun, the spacecraft will gradually spiral away from the Sun. Over an 18-month period it will follow the trajectory shown below.

The numbers show the distance from the Sun in astronomical units. After 18 months the spacecraft will be approximately 1.6 AU from the Sun. This is roughly the distance to Mars.

Example 2

This is the same as the previous example with the exception that the sail is orientated to decelerate the spacecraft in its orbit

In this case assuming the orientation remains at 45 degrees to the direction of the Sun, the thrust provided by the sail will cause the spacecraft to steadily lose energy and it will spiral inwards towards the Sun. Over a 12-month period it will follow the trajectory shown below.

After 12 months the spacecraft will be only 0.56 AU from the Sun. This is between the orbits of Venus and Mercury.

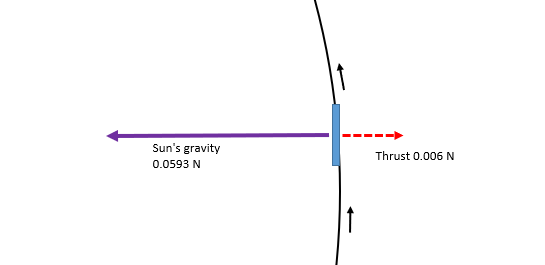

Example 3

In this case, once again the spacecraft has a mass of 10 kg and starts off in a circular orbit at a distance of 1 AU from the Sun. This time the sail is orientated at an angle of 90 degrees to the direction of the Sun and produces a thrust of 0.006 newtons.

In this case the spacecraft’s orbit changes shape from circular to elliptical. Its closest distance from the Sun is 1 AU and its furthest is 1.25 AU. It takes 460 days to complete its new orbit.

And Finally…

I hope you have enjoyed this post. I will post more about solar sails in the coming months and will talk about the three successful missions where spacecraft were powered by solar sails. I have also created a video which goes into this topic in greater detail.

This is so interesting! I’ll have to read the Revenger series by Alistair Reynolds again, this time not just glossing over the nitty gritties of how the solar sails work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes it is an interesting topic with promise for the future

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting because the answer to the possibilities of such space travel i snot just blowing in the solar wind.

LikeLike

🙂

LikeLike

I know I’m a simple gardening soul, but I assume we’re talking unpersonned spacecraft? The mass of anyone added in – that would change the calculations a lot?

LikeLike

It certainly would change the calculations !! the ones I have put in are for a small light spacecraft!

If you add the weight of a human plus a space capsule with all the supporting systems needed, then you’re talking about a spacecraft weighing a least tonne.

So you would need a much much larger solar sail to provide a decent acceleration

LikeLike

I don’t think I ever fully understood the potential for solar sails before your post. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

You’re very welcome

LikeLike

[…] https://explainingscience.org/2025/09/21/solar-sails-fuel-free-space-travel/ […]

LikeLike