Many people think of a year as the period it takes the Earth to complete a single orbit around the Sun and for the cycle of the seasons to repeat themselves. However, when we look at this in more detail there are three different ways of defining a year, all based upon the Earth’s motion around the Sun and all of which give years of differing lengths. In this post I will talk about these different types of year.

But before I do this, it is worth saying a little about the Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

.

The Earth’s orbit around the Sun

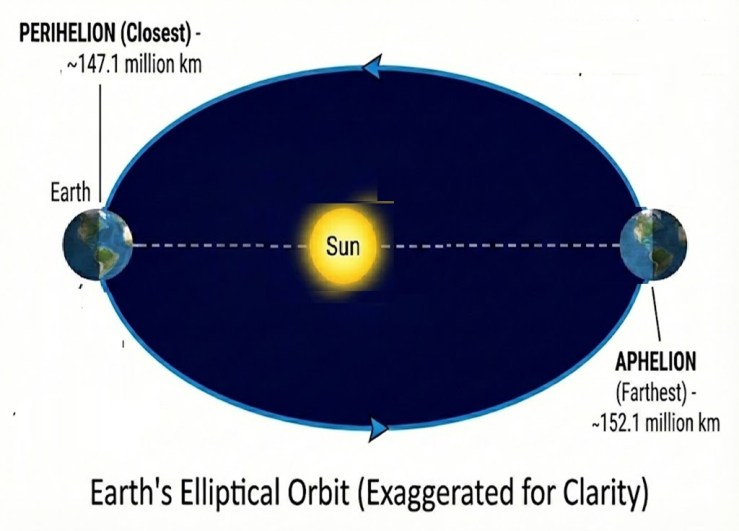

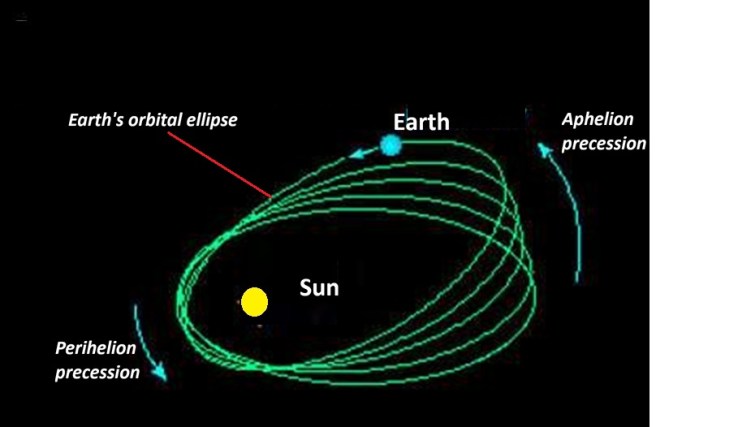

The Earth moves in an elliptical orbit around the Sun.

- At its closest (its perihelion), which occurs around January 3, it is 147.1 million km away.

- At its furthest (its aphelion) which occurs around July 5, it is 152.1 million km away. [1]

At perihelion the Sun is 7% larger in area in the sky and so the intensity of its radiation reaching the Earth is 7% higher than at aphelion.

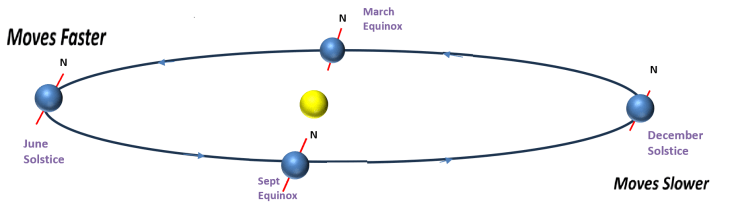

The Earth’s elliptical orbit and uneven speed means the time intervals between the two equinoxes, when the length of day and night are almost exactly 12 hours everywhere on Earth, are not the same.

It takes 178.845 days for the Earth to travel from the September equinox to the March equinox during which time it is moving faster than its average speed and the distance travelled is less than half an orbit.

By comparison to do the return leg of the journey from the March equinox back to the September equinox takes 186.388 days. During this time, the Earth is moving slower than its average speed and the distance travelled is more than half an orbit.

The Sidereal year

The sidereal year is the length of time it takes for the Earth to complete a single orbit, on average 365.256363 days. However, the Earth’s orbital period and thus the length of the sidereal year can vary a little. The gravitational pull of other planets can temporarily speed it up or slow it down in its orbit. [2] This can make a particular sidereal year a few minutes shorter or longer than the average value.

In addition, the Earth is gradually getting further from the Sun, spiralling out at a rate of 1.33 cm per year. This is happening for two reasons.

- The key reason is that the Sun is losing about 5.6 million tonnes of mass per second as it converts hydrogen fuel into helium and in addition a small amount of the Sun’s outer layers are blown out into space in the solar wind.[3] This mass loss causes its gravitational pull on the Earth to weaken causing the outwards spiralling.

- Secondly, tides raised by the Earth on the Sun cause a small amount of the Sun’s rotational energy to be transferred to the Earth boosting it to a higher orbit. But this effect is negligible compared to solar mass loss.

This slow spiralling out increases the average length of the sidereal year at a slow and steady rate of 5.61 microseconds per year. In ten million years’ time it will be nearly one minute longer than it is today.

The Tropical Year

The tropical year (also called the solar year) is the most important of the years defined by the Earth’s orbit around the Sun. It is the year that we approximate our civil calendar to. The tropical year is slightly shorter than the sidereal year.

Definition of the Tropical Year

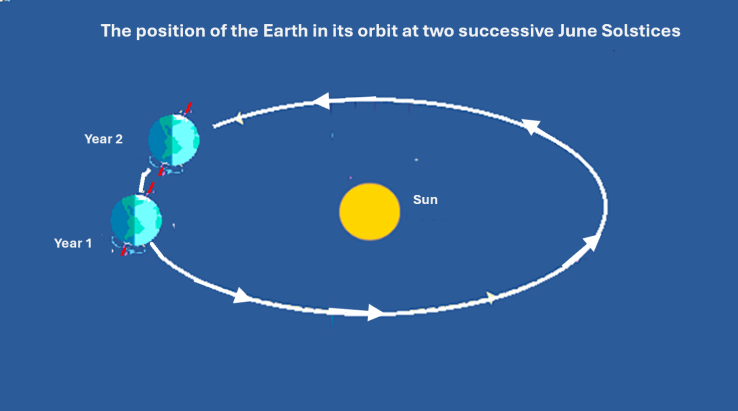

If we take the June solstice , the start of Northern Hemisphere summer when the Earth’s North Pole is tilted at its greatest angle towards the Sun and the Northern Hemisphere has its most daylight then after one tropical year the Earth’s North Pole is once again tilted towards the Sun

Dates and Times of the June Solstice for locations at different longitudes.

The tropical year can be defined as the interval between one June solstice and the following one. But it can be defined in other ways. It can alternatively be considered as the interval between one March equinox and the following one, or indeed between any other apparent position of the Sun and the same position recurring a year later.

Difference in length between the Tropical and Sidereal Year

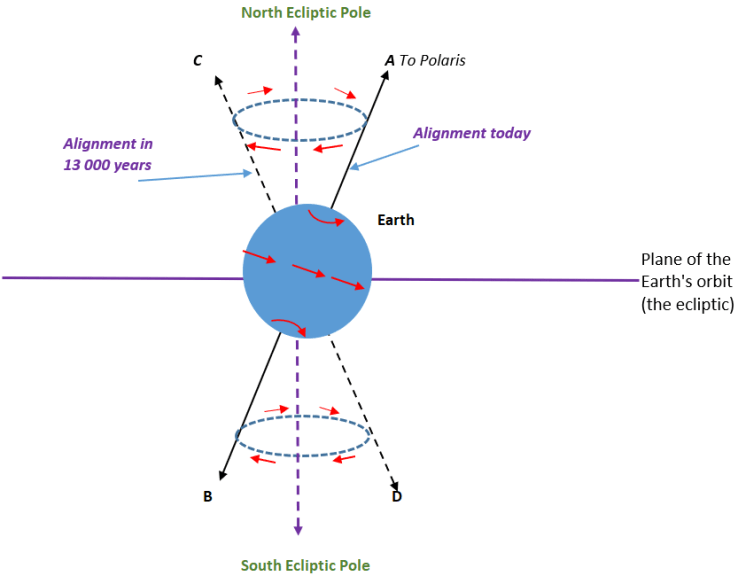

The orientation of the Earth’s rotation axis isn’t fixed. If we look “downwards” over the Earth’s Northern Hemisphere, over a 25 800 year cycle the North Pole moves in a clockwise direction around a point known as the North Ecliptic Pole. This is known as the precession of the Earth’s axis.

If we consider the June Solstice, when the Earth’s North Pole is at its maximum tilt toward the Sun, precession means the Earth needs to perform slightly less than one orbit for the North Pole to be at its greatest tilt again.

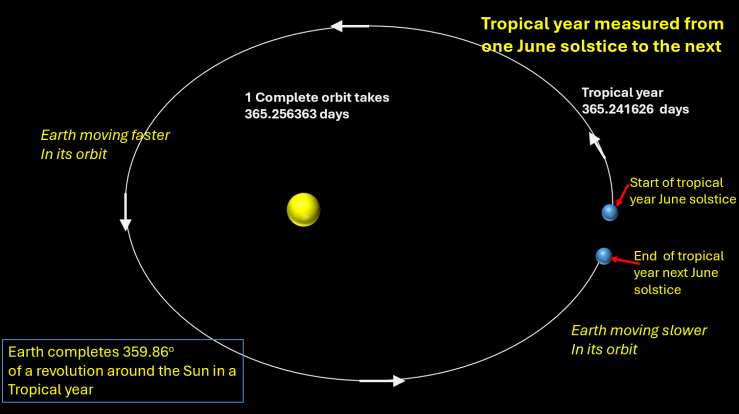

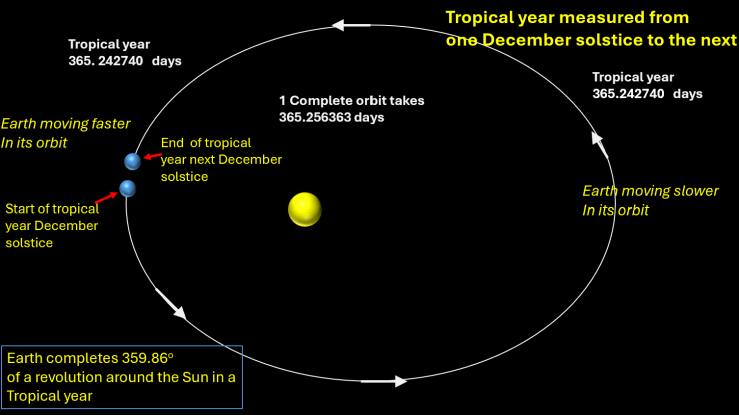

The length of a tropical year varies according to how it is defined. For example, from one June solstice to the next it is 365.241626 days, However, from one December solstice to the next it is 365.242740 days, 96 seconds longer. At first sight this variation might seem a bit odd. But it makes sense if you think about the Earth’s uneven speed in its elliptical orbit. As mentioned previously it moves faster when closer to the Sun and slower when further away.

To complete a tropical year, the Earth only goes round 359.986° of an orbit and misses out the final 0.014° (=1/25 800th). The June to June tropical year is shorter than the December to December one, because, in this fraction of an orbit, the Earth has travelled a slightly further distance and at a slightly faster than average speed.

Tropical Year measured from one June solstice to the next

Tropical Year measured from one December solstice to the next

The Length of the Tropical Year

If we measure the length of the tropical year at other times we get slightly different values:

- Measured from one March equinox to the next, the tropical year is 365.242374 days long.

- From one September equinox to the next, it is 365.242018 days long.

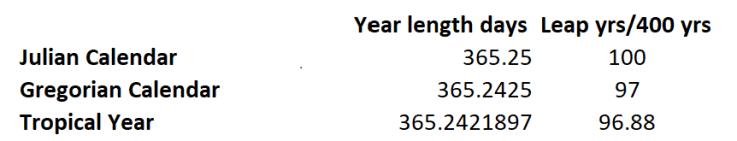

The mean value of the tropical year averaged out over the entire year is 365.2421897 days.[4]

A further complexity is that the rate of precession of the Earth’s axis isn’t constant and is currently speeding up slightly. This means the average length of a tropical year is getting shorter by 5 milliseconds per year. In about 10000 years’ time this trend will reverse, and it will start getting longer again. On top of this there is the small steady increase in the length of the tropical year of 5.61 microseconds per year due to the lengthening of the Earth’s orbital period because of solar mass loss.

The Calendar Year

The Calendar that most of the world’s population use for civil purposes approximates the tropical year.

In 45 CE Julius Caesar introduced a calendar in which there are 365 days in a year and a leap year every 4 years. This is known as the Julian Calendar and was used by all Christian countries until 1582. It results in a year which is on average 365.25 days long, whereas the length of the tropical year is 365.2421897 days (roughly 0.0078 days shorter). This slight difference caused the Julian Calendar to diverge from the natural cycle of the seasons (which is based upon the tropical year) at the rate of 7.8 days per thousand years.

Between 325 CE, when the Julian calendar was first used by the church to define the date of Easter and 1582, the calendar had drifted back by 10 days. By then the March equinox, the first day of the Northern Hemisphere spring, occurred on March 11 whereas in 325 CE it had been on March 21. The spring equinox is used to calculate Easter, so the date range on which Easter could fall had drifted back by 10 days.

The Gregorian Calendar

To prevent the calendar from drifting any further from the seasons, in 1582 Pope Gregory XIII introduced a refinement where a century year (e.g. 1600, 1700, 1900, 2000, 2100) could only be a leap year if it were divisible by four hundred. So, 1700, 1800 and 1900 would not be leap years, but 1600 and 2000 would. He also proposed that the calendar be brought back in line with the seasons so the spring equinox would once again fall on or around March 21. This required that 10 days be omitted when moving from the old to the new calendar. Pope Gregory’s calendar, which is the civil calendar for the vast majority of the world’s population , is called the Gregorian calendar in his honour. On averageeach year is 365.2425 days, only 0.000 31 days longer than a tropical year.

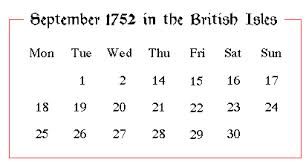

The Gregoriancalendar was adopted by the Catholic countries in Europe in 1582. Spain, which at the time included Portugal and much of Italy, adopted it on 4 October 1582. The next day was 15 October 1582, the days from 5 October to 14 October were omitted. In 1752 Great Britain and its colonies, which included America, switched to the Gregorian calendar on Wednesday 2 September 1752, which was followed by Thursday 14 September. The eleven days from 3 September to 13 September were missed out.

But even though the Gregorian calendar is a much better match to the tropical year than the Julian calendar, it is not a perfect fit, and it will be necessary to omit more leap years in future to keep it fully in line with the seasons.

For each calendar the average length of year is given in days. The leap yrs/ 400 yrs column gives the number of leap years over a four hundred year period.

The rules for the Gregorian calendar give slightly too many leap years, an additional 0.12, over the four hundred year cycle. So, a leap year needs to be omitted every 3300 years to keep the calendar fully in line with the seasons. As discussed in my next post The Earth’s rotation and time, over a longer period the gradual lengthening of the day means that there will be fewer days in a tropical year, and leap years will be needed less frequently.

The Anomalistic year

The anomalistic year is the time taken for the Earth to complete one revolution with respect to its apsides, (this is a term astronomers give collectively for the aphelion and perihelion). By convention, it is normally defined as the time between successive perihelions.

The gravitational effects of other planets in the Solar System, in particular the giant planets Jupiter and Saturn cause the perihelion (and the aphelion) to move in an anticlockwise motion when viewed from above the plane of the Earth’s orbit.

The gradual movement of the perihelion means the average duration of the anomalistic year is 365.259636 days, longer than the other two types of year. This means the Earth’s perihelion drifts later by 25 minutes each year compared to the tropical year [5].

In roughly 10 500 years’ time perihelion will occur at the time of the June solstice (the Northern Hemisphere summer solstice) and aphelion will occur at the time of the December solstice (the Northern Hemisphere winter solstice). This is the opposite way round to when they occur now.

As a result, the extra radiation caused by the Earth being closer to the Sun in the summer months means the climate in the Northern Hemisphere will become hotter in summer leading to more glacial melting. The reduced radiation caused by the Earth being further from the Sun in winter means in the Northern Hemisphere it will become colder in the winter months, i.e. more extreme seasons. However, a mitigating factor is that the Earth’s orbit is becoming less elliptical over a 100 000 year cycle and in 10 500 years’ time there will be a smaller difference between perihelion and aphelion.

This is an interesting topic which I could write many posts about and if you want to know more it there is a good non-technical summary on how changes in the Earth’s ellipticity, alignments of its axis and axial tilt affect climate in the article Milankovitch (Orbital) Cycles and Their Role in Earth’s Climate which is on the NASA website [6]

References

[1] Kher, A. (2019). Perihelion, Aphelion and the Solstices. [online] Timeanddate.com. Available at: https://www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/perihelion-aphelion-solstice.html.

[2] Meeus, J. (1998). Astronomical algorithms. Richmond, Va.: Willmann-Bell.

[2] http://www.timeanddate.com. (2026). A Year Is Never 365 Days. [online] Available at: https://www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/tropical-year.html.

[3] Siegel, E. (2020). Ask Ethan: Does Earth Orbit The Sun More Slowly With Each New Year? Forbes. [online] 4 Dec. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2020/12/04/ask-ethan-does-earth-orbit-the-sun-more-slowly-with-each-new-year/.

[4] The Tropical Year and Solar Calendar Borkowski, K. M( 1991) Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 85, NO. 3/JUN, P.121, 1991 [online] Available at: https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1991JRASC..85..121B [Accessed 17 Feb. 2026].

[5] Laskar, J., Robutel, P., Joutel, F., Gastineau, M., Correia, A. C. M., & Levrard, B. (2004). “A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the Earth.” Astronomy & Astrophysics, 428(1), 261–285.

[6] NASA Science (2020). Milankovitch (Orbital) Cycles and Their Role in Earth’s Climate. [online] science.nasa.gov. Available at: https://science.nasa.gov/science-research/earth-science/milankovitch-orbital-cycles-and-their-role-in-earths-climate/. [Accessed 17 Feb. 2026].

Hi Steve,

We have to admire the remarkable accuracy of Pope Gregory’s calculations. In the days when the only computational device was the abacus – or the pencil! – the observations & their processing would have been a formidable achievement.

You didn’t mention it – and fair enough it hasn’t anything to do with the science – but at the time there were riots among the general population about the perceived deliberate deprivation of eleven days from their lives!

David.

LikeLike