Updated 28 January 2026

Although the Universe may be infinite in extent, in the generally accepted Big Bang cosmology we are only able to see a small fraction of it. We call this small fraction we can see the observable universe. Outside the boundary of the observable universe lies the unobservable universe – a region of space which is too far away for us to have any direct information about

Field of distant galaxies – Image Credit NASA

There are two types of boundary of the observable universe ( which astronomers call cosmological horizons), which provide limits to how far away we can see. The purpose of this post is to explain them in a non-technical way. I hope I succeed!

(1) The Particle Horizon

As discussed in my earlier post on distances in cosmology , when we look at a distant galaxy its light will have taken many millions (or even billions) of years to have reached us. If we could construct a cosmological-sized ruler between the distant galaxy and the Earth then we would measure a quantity known as the proper distance to the galaxy.

Because the Universe is expanding, the proper distance between two distant objects increases with time. In the example below, light is emitted from a galaxy which 300 million years ago was at a proper distance of 294 million light years from Earth. However, the Earth is moving away from the emitted light photons all the time they are travelling towards us. So these photons actually travel 300 million light years to reach Earth. When they reach us the proper distance of the galaxy will be 306 million light years.

Definition of the Particle Horizon

The particle horizon is the theoretical maximum proper distance we can see to at the current time. It is a spherical shell approximately 46.5 billion light years in radius around the Earth. When we look at distant objects we are looking back in time and light from an object at the particle horizon will have been emitted at the beginning of the Universe and will have been travelling towards us for the entire age of the Universe.

All the objects we observe today lie inside the particle horizon, which forms the boundary of the observable universe. If an object lies beyond the particle horizon, then the Universe is not old enough for its light to have had enough time to reach us.

At the exact instant of the Big Bang the particle horizon would have been zero and as the Universe ages the particle horizon increases. This is for two reasons.

(1) As the age of the Universe increases, light can travel a greater distance before it reaches us.

(2) Because the particle horizon is the proper distance of the furthest object we can see, due to the expansion of the Universe, the proper distance between two distant objects increases.

The time axis shows the time since the Big Bang, the purple dashed line marks the current particle horizon.

The Surface of Last Scattering

In reality, we cannot see all the way to the particle horizon. As discussed in the history of the Universe from the Big Bang, the early Universe was too hot for atoms to exist. It contained a plasma of positively charged hydrogen and helium ions and negatively charged electrons. Electromagnetic radiation, of which light is an example, cannot pass through plasma.

The oldest radiation we can detect is the cosmic microwave background (CMB) which was emitted when the Universe was only 400 000 years old, at which time it had cooled sufficiently for individual atoms to exist allowing light to pass through unimpeded. The photons in the CMB we observe today have been travelling towards us since this time and were emitted from a spherical shell of points, known as the surface of last scattering, which nows lies at a proper distance of approximately 46 billion light years from Earth.

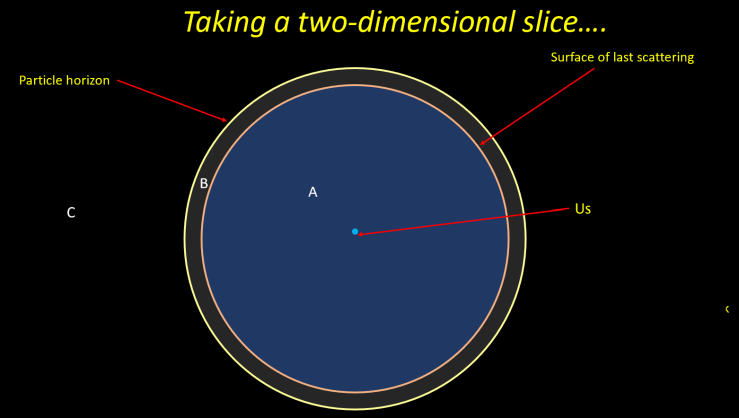

Electomagnetic radiation cannot pass through the hot plasma in the early Universe. Therefore, only light emitted from region A within the surface of last scattering can be seen. However neutrinos (which are very light particles ) emitted from region B outside the surface of last scattering can be detected. Nothing from region C outside the particle horizon can ever reach Earth,

(2) The Cosmic Event Horizon

The Hubble Sphere

Because the Universe is expanding, the further away an object is the faster it is receding from us.

There is a relationship between the velocity a galaxy is moving away from us and its distance. This is known as Hubble’s Law and is expressed as

v = HoD

where

- v is the velocity an object is moving away from us

- D is its distance

- Ho is the Hubble constant. If v is measured in kilometres per second and D is in megaparsecs (Mpc) (1 Mpc =3.26 million light years) then Ho is approximately 70 km/s per Mpc. The Hubble constant measures how fast the Universe is expanding.

Uing Hubble’s Law at a separation from us of 4,300 Mpc ( 14 billion light years) a galaxy will be receding from us at the speed of light. This is distance is known as the Hubble radius. The Hubble sphere is sphere centred on the Earth of radius equal to the Hubble radius. So, at the boundary of the Hubble sphere an object is receding from us at the speed of light.

In reality, the Hubble constant isn’t a constant as its value changes over time. So it is more correctly called the Hubble parameter H(t). The Hubble constant is the value of the Hubble parameter today. In the standard model of the Universe known as lambda cold dark matter the value of the Hubble parameter is gradually decreasing,

The cosmic event horizon is the maximum proper distance from us from which light emitted now will reach us at some distance time in the far future.

- If an object lies closer than the cosmic event horizon then its light will reach us.

- If an object lies further away than the cosmic event horizon then it so far away that light emitted now will never reach us.

If the Hubble parameter didn’t vary over time, then the cosmic event horizon would be the radius of the Hubble sphere (14 billion light years). In most cosmological models, even though the Universe is expanding, the value of the Hubble constant falls over time. The net effect of this is that the event horizon is larger than the radius of the Hubble sphere and the difference between the event horizon and the Hubble sphere changes over time.

The graph below shows how the event horizon changes over time. In the current model of the Universe the event horizon will gradually increase with time but at a slower and slower rate reaching a maximum value of around 18 billion light years.

Related Posts

I hope you have enjoyed this post. For further reading, here are some posts on related topics.

- What do we actually mean by “distance” when we are dealing on the vast scales which occur in cosmology.

- Dark Energy the energy accelerating the Universe’s expansion

- A brief history of the Universe from the Big Bang until the the present day

- Mathematical details on the cosmic event horizon.

There is a video covering the material in this post on the Explaining Science YouTube channel

There is a short video on the history of the Universe after it was one second old on the Explaining Science YouTube channel.

Reference

For more technical information on the particle horizon and cosmic event horizon, the following paper is worth reading.

Davis, T A and Lineweaver, C H (2003) Expanding Confusion: common misconceptions of cosmological horizons and the superluminal expansion of the Universe, Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0310808 (Accessed: 30 April 2021).

[…] call this distant boundary the Cosmic Horizon. It represents the absolute edge of what we can see in the universe. Because space at this distance […]

LikeLike

[…] moving through space faster than light. Eventually, most of them will cross a boundary called the cosmic event horizon. Once they do, their light will never be able to reach us, not even given infinite time. We can […]

LikeLike

[…] The observable universe has an apparent edge, called the cosmological horizon, which is about 46.5 billion light-years away from us in every direction. However, this isn’t a real boundary. It’s just the limit of […]

LikeLike

[…] “Hubble Sphere.” Explaining Science, 5 Sep. 2022, https://explainingscience.org/2021/04/30/cosmic-horizons/ […]

LikeLike

[…] Cosmic Horizons […]

LikeLike

[…] cosmic horizon is a sphere 46.5 billion light years away centered on Earth (Cosmic Horizons). This is the distance that we are able to […]

LikeLike

Hello Steve! Great explanation of the differences between cosmic horizons. Maybe you could share your thoughts on how the universe’s expansion will affect the number of galaxies visible in the future. Ethan Siegel argues that the number of galaxies observable, even if only briefly, will double over time (https://bigthink.com/starts-with-a-bang/how-much-of-the-unobservable-universe-will-we-someday-be-able-to-see/). This seems hard to believe, given that the expansion of space is moving everything away from the observer, including every galaxy currently beyond 46.5 billion light-years, at speeds far exceeding the speed of light. It would be plausible if these objects were stationary while the observable universe expanded, but that’s obviously not the case. These galaxies are apparently receding as well, and at much higher recession speeds than the imaginary boundary of the observable universe. Is Mr. Siegel mistaken in his assumption that these distant galaxies will somehow end up within the future cosmic event horizon? I’d appreciate your insights on this. Thank you in advance!

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment.

I have attached a link to this paper also referenced ib my post. It covers the material in much more technical detail.

https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0310808

Just to recap the cosmic event horizon is the distance of the most distant objects from which we will ever be able to light from emitted now.

The particle horizon at a given time is the current distance to the most distant object we can see.

The particle horizon can be larger than the event horizon because we can see the light from .

galaxies lemitted a time long ago but many of these galaxies are so far away and are receding so fast we will never be able to see light from them emitted today.

As time passes we can see more distant galaxies but the light from them will have been emitted a long time ago.

LikeLike

[…] Cosmic Horizons | Explaining Science […]

LikeLike

[…] Cosmic Horizons | Explaining Science […]

LikeLike

I wish U had a bigger graph of particle horizon vs time,

so I could see, easier/ly, what its size was at each 1 By mark.

LikeLike

[…] A conspiração da Terra plana pode não conter tanta água, mas o universo pode realmente ser muito mais plano do que você pensa. A ideia de um universo geométrico plano e infinito é apoiada pela teoria da relatividade geral de Einstein, que denota que a velocidade da luz é constante, não importa quão distorcido o espaço-tempo se torne devido à atração gravitacional de objetos como estrelas ou buracos negros. Também faz mais sentido, uma vez que a quantidade total de “universo” existente é definida por um horizonte de eventos – uma fronteira através da qual nenhuma luz pode escapar – que está em constante expansão em todas as direções a uma velocidade que é notavelmente mais rápida que a velocidade de luz (através Explicando a Ciência). […]

LikeLike

[…] said Loeb. “As a result of the expansion of the universe, this edge is currently located 46.5 billion light years away. The spherical volume within this boundary is like an archaeological dig centered on us: the […]

LikeLike

For the fun of it, try this: Let a proton mass and an electron mass be in

stable circular gravitational orbit around their common center of mass.

Let the proton’s orbital angular moment be hbar. Set GMpMe/R^2 =

mu Vp^2 /R, where mu is the reduced mass, R is distance between Mp

& Me, Vp is Mp’s velocity, and rp is radius of Mp’s orbit.

NB: hbar = Mp*rp*Vp. Solve for 2*rp (the diameter of Mp’s orbit).

Convert this answer into light years and notice your jaw dropping.

LikeLike

Yes it will be pretty big orbit! But then gravity is such a weak force

LikeLike

Is there an equation with which you can enter a given age of the universe and calculate what the event horizon was at that time?

LikeLike

Hi Jay,

Thanks for your comment. I have created a page which hopefully will answer your question

LikeLike

May I ask a question?

Can you tell how old the universe is when the particle horizon is 26.4 Gly?

LikeLike

Firstly, as discussed in the post

The particle horizon is the theoretical maximum proper distance we can see to at the current time. It is a spherical shell approximately 46.5 billion light years in radius around the Earth. When we look at distant objects we are looking back in time and light from an object at the particle horizon will have been emitted at the beginning of the Universe and will have been travelling towards us for the entire age of the Universe.

Secondly,

The age of the Universe depends on the various parameters in our model of the Universe. Essentially what we do is measure its current density, composition and rate of expansion and work backwards to time when it had an extremely high density. The following link may prove useful

https://wmap.gsfc.nasa.gov/universe/uni_age.html

LikeLike

I did not read the entire content, but how did the particle horizon reached 46.5 billion light years in radius IF the age of universe is only at 13.8 billion years since big bang? Should it not be only atmost 13.8 billion light years(the farthest the light would have traveled since big bang)?

LikeLike

Hi Rodel, that is due to cosmic expansion of the fabric of space, so while the cumulative separation could be at well in excess of light speed, the objects themselves are just in their normal orbital peculiarities. The classic analogy example is leavening raisin dough. This holds true under both SCM-LCDM consensus and the competing SPIRAL cosmological redshift hypothesis and model.

LikeLike

Nice presentation Steve.

Please advise approximate LY distance of the original departure point radius, of the CMB radiation we see here and now, that has travelled 13B rounded LY to get here.

was it at that distance x at the end of 400k years after the start of the big bang? or the end of cosmic inflation?

also

what is the nearest known departure point of any light we see here and now that has ever been subjected to any comic expansion?

by definition any light arriving here and now that has any degree of cosmological redshift (CR) has been subjected to cosmic expansion, is that LY distance closer than to the nearest stellar object whose light has any CR?

distance where it is now and how much closer it was when the light departed it, please.

TY,

rm

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. The photons we now observe as the cosmic microwave background were emitted (or be absolutely precise “last scattered”) when the universe was ~ 400 000 years old. The photons were emitted from a spherical shell which at the time was located at a proper distance of roughly 45 million light from us. But, during the 13.8 billion light years they have been travelling, the expansion of Universe means that the region of space they were emitted from now lies at a proper distance of roughly 46 billion light years from Earth.

As stated in my post https://explainingscience.org/2020/12/10/dark-energy-an-unexpected-finding/, the expansion of the Universe means that distance between our own Milky Way galaxy and any object not gravitationally bound to us increases over time. Our galaxy together with Andromeda galaxy and numerous smaller galaxies form a gravitational bound structure known as the Local Group. If you want to know more about the Local Group the link below gives a reasonable overview

https://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/features/cosmic/local_group_info.html

Galaxies outside the Local Group (i.e. lying at a distance of more than ~5 million light years) will, in general show a cosmological redshift

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Dr. Hurley, very helpful, have a great week, rm

LikeLike

Very interesting. Could you please rewrite it without the assumption of a big bang, inflation and expansion. I really am curious about the outcome…

LikeLike

Hi Hakan,

it depends on the model and assumptions.

For example if SPIRAL cosmological redshift hypothesis and model, the entire universe approximates the visible universe, that we (Earth-moon-sun ecliptic are at the approx. center of, that has a maximum radius of 4B LY.

The universe attained mature size and density after 4/365(5781) a fraction of history.

For now assume the radius is 4B LY.

So by the end of 4B years of the universe having attained mature size and density, no more light will reach us that has ever been subjected to cosmic expansion.

LikeLike