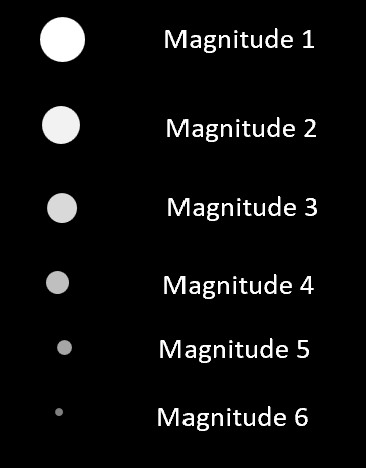

When measuring the brightness of objects in the sky, astronomers use the magnitude scale. The basis of the scale we use today was invented by ancient Greek astronomers. They classified all the stars into six magnitudes. The brightest stars were magnitude 1, the next brightest magnitude 2 and so on. The faintest stars visible to the naked eye had a magnitude of 6. The magnitude scale was unusual in that the lower the numeric value the brighter the object.

The ancient Greeks gave all stars magnitudes which were whole numbers. However, over the centuries it became clear that fractional magnitudes were needed because for example not all stars assigned a magnitude of 1 have the same brightness.

Standardising the Scale

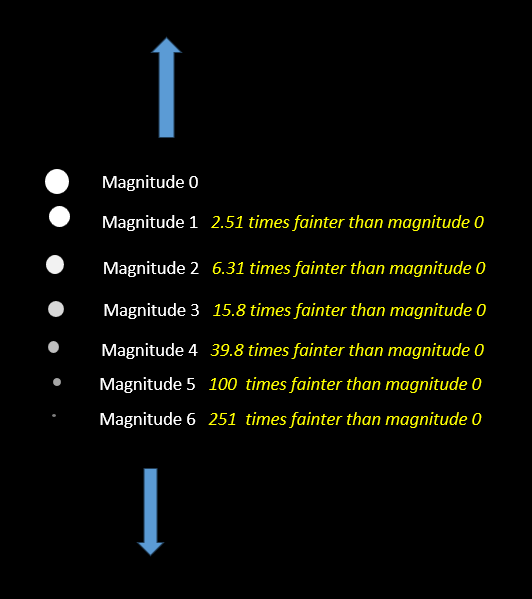

In 1856, the British astronomer Norman Pogson standardised the magnitude scale to make an increase in magnitude of 5 a decrease in apparent brightness by a factor of 100 and vice versa. So for example, a star of magnitude 6 is a hundred times fainter than one of magnitude 1. As photometry, measuring the brightness of objects developed, it became clear that there was more than a hundred-fold variation between the brightest and the faintest stars. So, the scale was extended so that the brightest stars had a magnitude of less than one. The brightest star in the sky, Sirius, has a magnitude of -1.46. Stars too faint to be seen with the naked eye have a magnitude value greater than 6.0.

Any scale must have at least one reference point. For example, on the centigrade scale 0o is the freezing point of water and 100o its boiling point. On Pogson’s scale the bright star Vega in the constellation Lyra was given a magnitude of zero and an increase in magnitude value of 1 a decrease in brightness of the fifth root of one hundred ( 5√100) which is roughly equal to 2.512.

The modern magnitude scale

Today, the magnitude scale is still by far the most widely used measure of the brightness of stars, despite having the counter intuitive property that the greater the value the fainter the object. As well as stars, the modern magnitude scale also applies to planets, asteroids, comets and even artificial satellites.

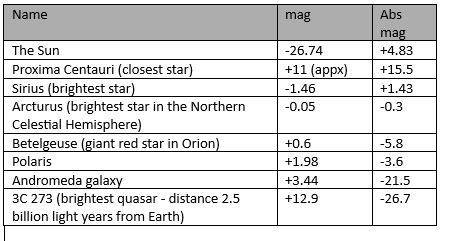

Magnitudes of Some Objects

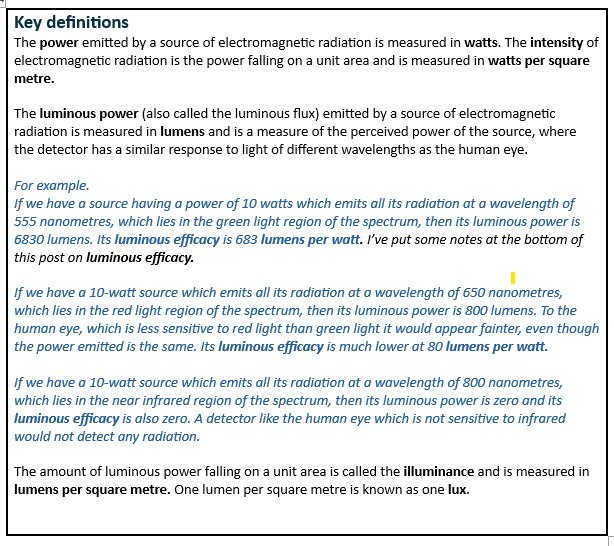

Although the term brightness is widely used even in scientific literature, it can be ambiguous. In precise scientific terms, the magnitude scale is a measure of illuminance.

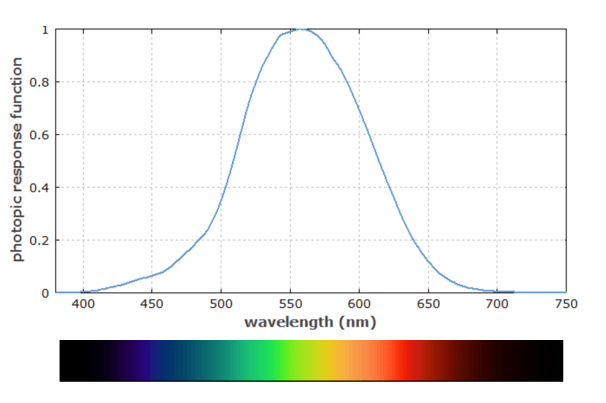

The lumen is a measure of the luminous power of visible light emitted by a source. The power at different wavelengths is weighted according to a standard model which approximates the human eye’s sensitivity to various wavelengths.

Illuminance is the luminous power per unit area and is measured in lumens per square metre. One lumen per square metre is also known as a lux.

Rather than being based upon Vega which is a slightly variable star, the zero point of the modern magnitude scale has an illuminance of 2.12 x 10-6 lux. For those of you interested in the mathematical detail, the following formula is used to convert from a magnitude the illuminance value in lux:

Where Ev is the illuminance and mv is the magnitude.

(Source https://janvangastel.nl/Astronomy/Formules.pdf)

The illuminance of the Sun is 105680 lux, a full supermoon is 0.308 lux. and the brightest star Sirius 8.17 x 10-6 lux which is 13 billion times less than the Sun. For comparison the illuminance 2 metres away from a 1500 lumen household light bulb is 29.8 lux, assuming its light is spread out equally in all directions.

Absolute magnitude

Early astronomers believed that all the stars were at the same distance from us. In the 19th and early 20th century it became clear, as the distances to more and more stars were measured, there was a vast variation between them. To provide a measure of real brightness, absolute magnitude was introduced. The absolute magnitude is the magnitude a star would have if it were placed 10 parsecs (32.6 light years) away from us.

The magnitude we observe on Earth became known as the apparent magnitude. For example, the Sun which has an apparent magnitude of -26.74 has an absolute magnitude of only 4.83. It is only very bright because it is close to us and, if it were 10 parsecs away, it would be an insignificant star.

Absolute magnitude applies not just to stars but to all astronomical objects which emit their own light. For, example, hot clouds of glowing gas, entire galaxies and distant objects such as quasars.

Absolute magnitudes of some objects

The absolute magnitude of large objects, such as the Andromeda galaxy which is roughly 150 000 light years in diameter, is calculated assuming all of its light is concentrated into a small source.

Absolute magnitude of planets

Objects which don’t emit their own light and shine by reflected light such as planets, asteroids, comets and indeed artificial satellites would be completely invisible at a distance of 10 parsecs. The concept of absolute magnitude doesn’t apply in the same way. Their brightness depends on the following.

- The object’s surface area.

- The distance from the observer.

- The distance from the Sun.

- The fraction of the light hitting it which is reflected back rather than being absorbed – its albedo.

- The fraction of the object which is illuminated – its phase.

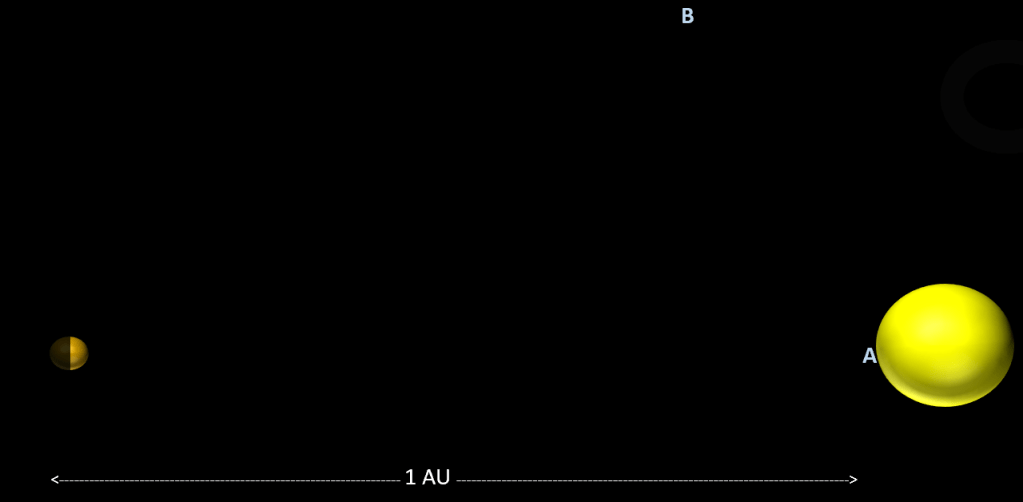

The equivalent of absolute magnitude for objects which shine by reflected light is the H value. This is the apparent magnitude the object would have if

- it were 1 astronomical unit from the observer (1 astronomical unit is the mean distance between the Earth and the Sun approximately 150 million km)

- it were also 1 astronomical unit from the Sun and

- it were 100% illuminated – full phase.

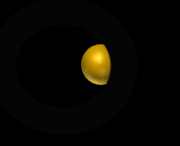

However, the only way it would be possible to satisfy all three conditions would be for the observer to be located on the surface of the Sun (A). At location such as B, which is also 1 AU from the object. It would be less than 100% phase.

How the planet would appear from location B

H values of some Solar System objects

Source https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/

Just to confuse things, astronomers sometimes use the term absolute magnitude for Solar System objects. In which case they mean the H-value.

If you want to find out more about the factors whcich brightness of Solar System objects then I have put together this video on the brightness of Venus.

Magnitudes at other wavelengths

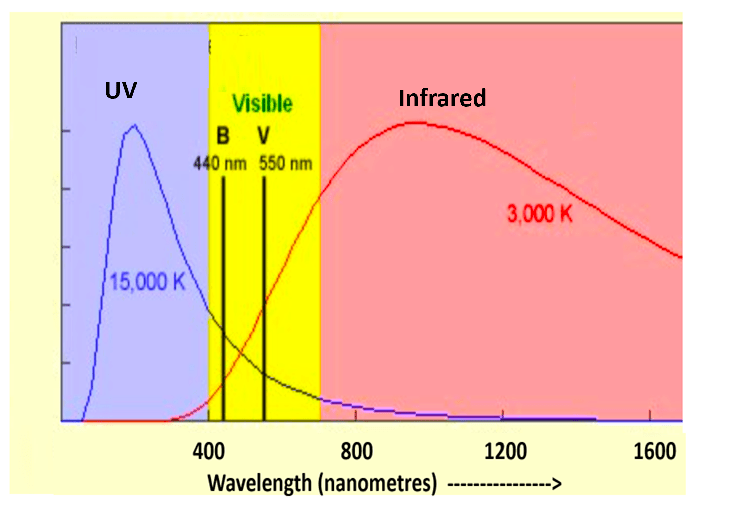

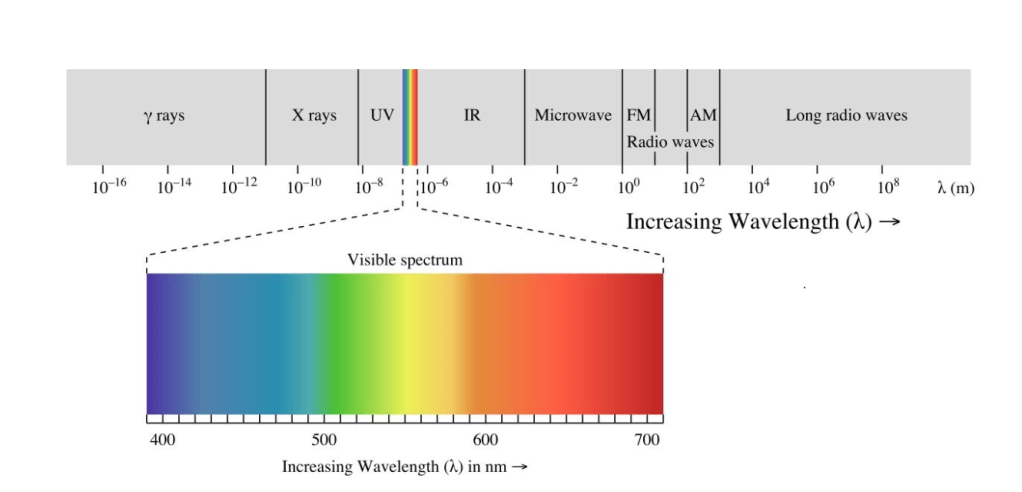

Up until now, I have only considered magnitudes based upon what astronomers call the V-band. This approximates to how the human eye has different sensitivity to light at different wavelengths. These are more precisely called Visible magnitudes or V- magnitudes.

Stars which are much hotter than the Sun radiate most of their energy at shorter wavelengths primarily in the ultraviolet and their visible light is mainly at the violet and blue range of the spectrum.

Stars which are much cooler than the Sun radiate most of their energy at longer wavelengths primarily in the infrared and their visible light is mainly at the red end of the spectrum.

For this reason, astronomers use magnitudes measured at other wavelengths. Some examples are.

- Blue or B- magnitudes based upon light received over a range of wavelengths in the blue region of the spectrum centred on 440 nanometres.

- Red or R- magnitudes based upon light received over a range of wavelengths in the red region of the spectrum centred on 650 nanometres.

The term magnitude, without any further qualification is always assumed to be an apparent magnitude in the V-band.

Luminosity

Stars emit most of their energy in the visible light, infrared and UV regions of the spectrum – with energy emitted at other wavelengths making a much smaller contribution. However, some objects emit large amounts of energy at other wavelengths. For example, large black holes are surrounded by disks of matter heated to such high temperatures (millions of degrees Celsius) that they emit large amounts of their energy as X-rays.

The luminosity is the power emitted by an object such as a star, galaxy or a quasar summed up over the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

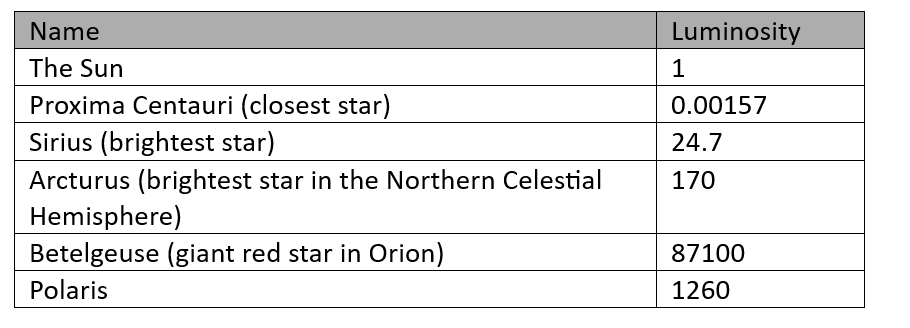

The standard unit of power is the watt. However, in watts the power emitted by stars are very large numbers. Therefore, luminosities are usually expressed on a scale where the luminosity of the Sun (3.828×1026 watts) is given the value of 1.

Some luminosities

And Finally…

I hope you’ve enjoyed this rather lengthy post. If you’ve not done so before then please take a look at my YouTube channel YouTube.com/explainingscience

Notes

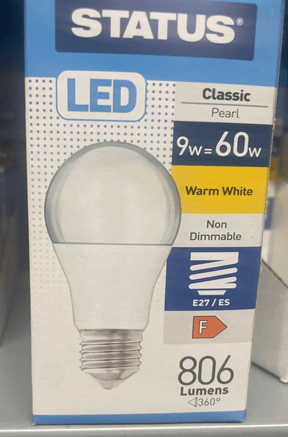

Forms of lighting other than traditional incandescent bulbs, where light is emitted from a hot filament, have become more common such as fluorescent lights and more recently LEDs. The amount of visible light produced is now expressed as a luminous power (in lumens) as well as the power consumed (in watts) to allow effective comparison across different types of lights.

LEDs have a far greater luminous efficacy (lumens per watt) than incandescent light bulbs and so are much more energy efficient. For example, this 9-watt LED lightbulb has a luminous power of 806 lumens. So, its luminous efficacy is 89.6 lumens per watt. It has the same luminous power as a 60-watt incandescent light bulb, which has a luminous efficacy of only 13.4 lumen per watt.

I am definitely a “non-scientist” (poet instead!), but I’m fascinated by astronomy and at least the basic concepts of astrophysics, so any information that you can provide that a poet’s mind can understand will be greatly appreciated!

LikeLike

Hi thank you very much for my your interest in my blog,

There are quite a number of videos on my YouTube channel (www.youtube.com/explainingscience)

I’ve put some of the less heavy ones in the “Popular Astronomy” playlist (link below) and as a non-scientist would I think it might well be worth you taking a look at them.

Steve

LikeLike

So nicely explained Sir, thank you!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Steve: As always a model of clarity – and your posts are often a useful reminder of the frequent mis-use in books and by journalists, of units & terms, sometimes by people who should know better.

In the table of Magnitudes of Some Objects, the entry for the abs. mag. of the Andromeda galaxy is a slightly whimsical one isn’t it. i.e. for an object of around 50kpc diameter, it’s not meaningful for an observer to be 10pc away from it; he’d still be in the middle of it. (But we know what you mean.)

David.

LikeLike

Hi David,

You raise an important point. For larger objects such as galaxies the absolute magnitude is calculated assuming that all its light is concentarted in one place…

I will update the post to reflect this

LikeLike

A very illuminating post. Thank you for those details.

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed the post

LikeLike