Updated 7 December 2025

The ashen light is a faint glow, which many people claim to have seen on the night side of Venus. The Italian astronomer Giovanni Riccioli (1598 -1671) first reported it back in 1643, 33 years after Galileo had made the first observations of Venus with a telescope and discovered the planet had phases like the Moon. Even today, it remains a mystery whether the ashen light is a real phenomenon. Four hundred years after Riccioli there is no firm photographic evidence of it but neither has its existence been totally ruled out.

The Ashen Light – what it is claimed to be.

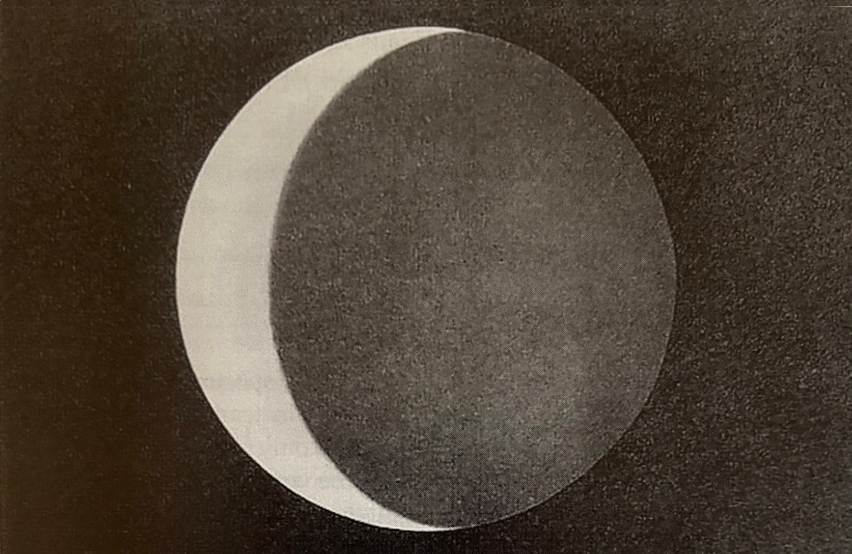

If you observe the Moon when it is in the crescent phase, at twilight or in full darkness then the part of the Moon which isn’t lit by the Sun is faintly visible because it is illuminated by light from the Earth This is called earthshine, and this long exposure photo of the Moon shows it. In fact, earthshine occurs at all phases of the Moon, but it is more noticeable in the crescent phase. The part of the Moon illuminated by earthshine cannot usually be seen by the naked eye in full daylight because it is too faint against the brightness of the blue daytime sky.

In this image, a long exposure was used to make the earthshine clearer. This has made the crescent part of the Moon, fully illuminated by the Sun, overexposed.

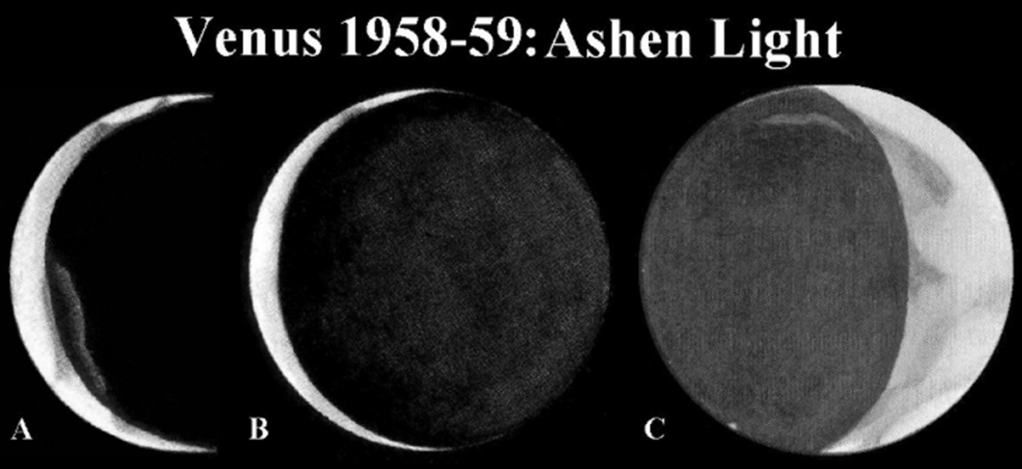

Over the centuries many astronomers claimed to have seen something similar when observing Venus. Looking through the eyepiece of a telescope, the illuminated crescent of Venus is a brilliant white. It has been claimed that the unlit part, rather than being completely black, is a very faint ashy grey colour hence the name “the ashen light of Venus”. William Herschel (1738 – 1822), who discovered Uranus claimed to have seen it. The drawings below were made in 1959 by the amateur astronomer Axel Firsoff (1910-81), who was a keen observer of Venus, from what he claimed to have seen through the eyepiece of his telescope. [[1]]

Many of my UK readers may remember Patrick Moore (1923 – 2012) who was the presenter of the BBC’s Sky at Night TV programme for many decades and did much to popularise astronomy. He believed the ashen light was real.

This diagram is based upon a sketch made by Patrick Moore when he observed Venus through his 15 inch telescope. It appears in his 2002 book Venus. [[2]] In the book he said that he had made the ashen light appear brighter than it appeared through the telescope’s eyepiece for additional clarity.

Possible Causes of the Ashen Light

If the ashen light exists then it cannot be caused by a full or near full earth lighting up the night side of Venus. On the near side of the Moon the Earth is very bright. A full earth viewed from the Moon is nearly four times the diameter of the full moon (viewed from Earth) and is around 40 times brighter. The brightness of the Earth in the sky lights up the lunar night.

At its closest, Venus is 40 million km from Earth, compared to the Moon’s average distance of 380 000 km -105 times nearer. Because the intensity of a light source falls as the square of the distance, a full earth would be at least 11 100 times fainter seen from Venus than from the Moon. It would almost certainly be too faint to produce any appreciable illumination of the night side of Venus and cannot be the cause of the ashen light.

With earthshine being ruled out, over the years a number of possible causes have been put forward for this phenomenon.

Lightning

From the 1980s to the 2010s, a popular hypothesis was that the ashen light was caused by lightning. Results from the Soviet Venera 9 and 10 spacecraft and ESA’s Venus Express detected many bursts of radio waves. This suggested that there might be frequent lightning strikes all over the planet. These could heat up and ionise the atmosphere causing a faint glow, which would be detectable on the night side of the planet. If lightning strikes were frequent enough then the entire night side might glow very faintly in visible light.

However, the Japanese Akatsuki mission carried the Lightning and Airglow Camera (LAC) which looked for evidence of lightning in part of the visible spectrum (wavelengths between 552 nm and 777 nm). It observed the night side of Venus for nearly 17 hours spread over multiple observing sessions. No flashes attributable to lightning were detected, whereas similar observations of the Earth’s night side would have yielded thousands of detections. [[3]]

Therefore, it would seem reasonable to rule out lightning as a cause of the ashen light.

Thermal emission from the night side.

All bodies emit thermal radiation over a range of wavelengths. The hotter the object the shorter the wavelength at which its peak emission occurs. Some examples are.

- The surface of the Sun has a temperature of about 5500 oC and its peak emission occurs at 502 nm, which is in the green light region of the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum.

- A traditional incandescent light bulb with a filament temperature of 2700 oC emits its peak radiation at 975 nm, which is in the near infrared region of the EM spectrum.

- The brightest star in the night sky Sirius has a surface temperature of about 9500 oC. Its peak emission occurs at 296 nm, which is in the UV region of the EM spectrum.

In his 2014 book The Scientific Exploration of Venus [[4]] the British planetary scientist Fred Taylor [1944 -2021], who had worked on the Pioneer Venus 1 spacecraft, suggested the night side of Venus which has a temperature of 464° C is just about hot enough to glow very faintly in visible light.

Outline of Taylor’s idea

The wavelength at which a body at 464 oC emits its peak thermal radiation is approximately 3.93 microns (3930 nm) which falls in the mid infrared (MIR) portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

The thermal (or blackbody) radiation emitted by an object at 464oC. In this diagram the mid infrared has been defined as wavelengths between 2.5 and 12 microns (2500 nm and 12000 nm). However, the definition is somewhat arbitrary, and other sources give different definitions.

As well as the peak being in the mid infrared, most of the radiation emitted at other wavelengths lies in this region too. As we move to shorter wavelengths, into the near infrared and visible light regions, the intensity of the thermal radiation rapidly diminishes. For example, the fraction of the total power radiated in the visible light region (380 nm – 750 nm) is miniscule, only 0.000 0015%. Despite this rapid fall off, if we consider the region in the near infrared from 750 nm to 1000 nm, i.e. just beyond visible light, a body at 464 oC emits a very small but significant fraction (0.00045% of its power) in this region.

Since the 1980s astronomers have been taking images of the night side of Venus in the near infrared. There are regions in the infrared spectrum where there is relatively little absorption, allowing the thermal radiation from the hot lower atmosphere and the surface to pass through the dense cloud cover [[5]]. Near infrared observations cannot be taken in the Venusian day, because this weak thermal emission from the surface would be totally swamped by the Sun’s infrared reflected from the upper cloud layers.

Most people’s eyes cannot see radiation with wavelengths longer than 750 nm. However, Taylor pointed out that this isn’t a hard and fast cut off. The natural variation between individuals means that some people with stronger sensitivity to red light can see a little into the near infrared. He suggested that such people when they look through a telescope can see the weak near infrared thermal emission from the surface and this is the ashen light.

Taylor’s interesting suggestion has not been generally accepted. Although Earth- based telescopes can pick up this weak thermal emission, in reality the human eye would almost certainly not be able to detect it. The eye’s sensitivity to light falls off strongly at longer wavelengths. At a wavelength of 750 nm, at the visible light/ near infrared boundary, it is typically 10000 times less sensitive than it is to green light at 555 nm. However, as Taylor pointed out, there is some natural variation and for a small percentage of people their sensitivity does not diminish so rapidly. Even so, for those individuals who can see a little into the infrared their sensitivity would be almost certainly far too low to pick up this weak thermal emission. Interestingly, the surface of Venus has a temperature just below the Draper point (525oC) at which a heated body emits just enough visible light to glow a dull red colour in a darkened room.

Visible light is defined as electromagnetic radiation having a wavelength between 380 and 750 nm. The eye’s peak sensitivity occurs at 555 nm (the black line in the diagram) and falls rapidly either side of that. Although there is some natural variation, for most people the eye’s sensitivity drops to zero at wavelengths shorter than 380 nm (ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths) or longer than 750 nm (infrared (IR) wavelengths).

Airglow

Another possibility, which is more plausible than the previous two, is airglow. On the day side of Venus, atoms in the planet’s upper atmosphere are energized by the Sun’s radiation. They are then carried to the night side by atmospheric circulation. When they reach the night side, these excited atoms drop back to their ground state, releasing the stored energy as visible light. This is essentially the same phenomenon which causes aurora on Earth, and it has been detected by observations of the nightside of Venus, particularly those taken by the Parker Solar Probe during flybys of the planet in the early 2020s [[6]].

It is possible that during periods of high solar activity that there might be sufficient airglow to make the entire night side of Venus faintly visible through a telescope for someone with good eyesight. This could be the cause of the ashen light.

Is it an illusion?

It remains the case today that there is no firm photographic evidence of the ashen light. By this I mean that no one has taken a photograph through an Earth-based telescope showing emission from the night side of Venus in visible light. All that exists are drawings of what people claimed to have seen through a telescope eyepiece. The problem with trying to photograph it is that the sunlit side of Venus is very bright, and so needs a short exposure to capture, whereas the ashen light (if it exists) would be very faint and would need a very long exposure. In theory using a device called an occulting bar to block the bright sunlit part of Venus, leaving only the very faint unilluminated part visible might make it possible to photograph the ashen light but this has never been done successfully.

The ashen light might well be an illusion caused by optics in the telescope. Alternatively, the observer’s brain when seeing a crescent Venus but knowing the object is circular somehow fills in the dark part of the circle. The brain is deceived into thinking that there is a faint glow on the unlit part of Venus when in fact there isn’t.

On a final note, in 2022 Paul Able, director of the Venus and Mercury section of the British Astronomical Association (the organisation for active amateur astronomers in the UK) [[7]], said that in decades of observing Venus he had never seen the ashen light.

And Finally….

If you want to find out more about Venus, I have have revised, updated and expanded my e-book about our sister planet. To find out more and read a sample without any obligation to buy please click A Short Guide to Venus.

Related Posts

I hope you have enjoyed this post. It is part of series of Explaining Science posts on Venus. Other posts include:

- Why is Venus so bright compared to other planets

- How Venus appears from the Earth, its phases and the 584 day cycle

- Terraforming Venus so that humans could live and work there.

- Could humans live in the Venusian atmosphere? And why would they want to?

- The Transit of Venus

References

[1] British Astronomical Association (2012). Venus in 2011–12: 3rd Interim Report – British Astronomical Association. [online] Britastro.org. Available at: https://britastro.org/section_news_item/venus-in-2011-12-3rd-interim-report [Accessed 6 Nov. 2025].

[2] Moore, Patrick (2002). Venus. Cassell & Co.

[3] Lorenz, R.D., Imai, M., Takahashi, Y., Sato, M., Yamazaki, A., Sato, T.M., Imamura, T., Satoh, T. and Nakamura, M. (2019). Constraints on Venus Lightning From Akatsuki’s First 3 Years in Orbit. Geophysical Research Letters, 46(14), pp.7955–7961. doi:https://doi.org/10.1029/2019gl083311.

[4] Taylor, F.W. (2014). The scientific exploration of Venus. New York, Ny: Cambridge University Press.

[5] Allen, David A. and Crawford, John W. (1984) Cloud structure on the dark side of Venus. Nature, 307(5948), pp. 222-224.

[6] Wood, B.E., Hess, P., Lustig‐Yaeger, J., Gallagher, B., Korwan, D., Rich, N., Stenborg, G., Thernisien, A., Qadri, S.N., Santiago, F., Peralta, J., Arney, G.N., Izenberg, N.R., Vourlidas, A., Linton, M.G., Howard, R.A. and Raouafi, N.E. (2022). Parker Solar Probe Imaging of the Night Side of Venus. Geophysical Research Letters, 49(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1029/2021gl096302.

[7] Able P (2022). Nightside observations by the Parker Solar Probe: implications for the reality of the Ashen Light – British Astronomical Association. [online] Britastro.org. Available at: https://britastro.org/journal_contents_ite/nightside-observations-by-the-parker-solar-probe-implications-for-the-reality-of-the-ashen-light [Accessed 6 Nov. 2025].

My best guess is the existence of CO2 ice/snow at high altitudes at night in the atmosphere transmitting some light as Venus turns (very slowly).

LikeLike

🙂

LikeLike

PS: I expect the reaction of some viewers might be: “Well even supposing that’s true, why isn’t a similar thing seen on Mercury or the Moon?”

All I can suggest is that it’s because they’re not surrounded by a thick, fast-moving blanket of carbon dioxide, capable of spreading some of the longer-lived decay products.

David.

LikeLike

Thanks for this, I’m not sure I’ve ever really been aware of this phenomenon. Always a good day when I can learn something new!

LikeLike

😉

LikeLike

So interesting…… something I havent heard of before. But I’m one of the readers who remembers Patrick Moore (and hears the theme music to The Sky at Night in my head every time I squint up at the stars).

LikeLike

Yes Patrick Moore was a really character. A bit of an old-fashioned traditional English eccentric. Incredibly, he presented the Sky at night for 55 years! from 1957 until his death in 2012 at the age of 89!! This still remains the world record for the longest time presenting a single TV programme

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Steve,

I haven’t attempted to do the maths, but do you think the (non-solar) cosmic ray flux is sufficient to produce a very-occasionally-visible effect.

In the absence of any significant magnetic field, hearly all of the incoming particles (ionized nuclei) would interact with the upper layers of the atmosphere rather than being deflected. I suspect that unlike on earth, relatively few would reach the surface owing to the atmosphere’s high average density.

The shower of secondary particles would give rise to ionization that might possibly be detectable from a distance. Come to that, the planet’s inhabitants – had they existed– might justifiably have named this region the ionosphere!

David.

LikeLike

That is an interesting thought. I supect it probably wouldn’t but I need to do the calculations to confirm that

LikeLike